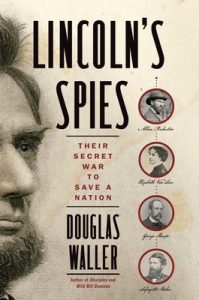

Lincoln’s Spies – Their Secret War To Save The Union

By Douglas Waller

Do you have some favorite Civil War books, books you have read and reread? I do. Are you always looking for more Civil War books that will become your favorites? I am. Are you looking for more books to add to your Civil War library? I always am. Would you like to know about a newly published Civil War book that is destined to become a Civil War classic, a book you will add to your Civil War library’s top shelf of favorites? I’d sure like to know about such a book.

Are you an experienced Civil War trooper of learning and reading, or are you a fresh recruit just beginning your campaign of Civil War education? Either way, you want to add good books to your Civil War library. I have a Civil War book recommendation for you. A good book about Civil War history that will become one of your favorites.

The new book is Lincoln’s Spies by Douglas Waller. It’s become one of my favorite Civil War books. Just as I’ve done, I think you will make space for it on your Civil War library’s top shelf of favorites.

Douglas Waller’s new book, “Lincoln’s Spies – Their Secret War To Save The Union” is a treasure chest of information for those who want to learn about the Civil War. This is a fast-paced book that will capture and hold your attention. Each page is packed with information and you will be eager to read the next page. I found it hard to put down.

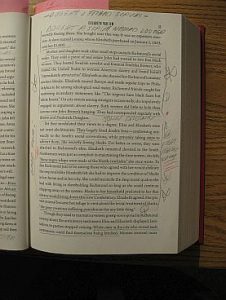

As I read this book I was constantly making notes in the margins, underlining sentences, and circling paragraphs with a good ol’ plain #2 pencil or a red pencil. I have facts, quotes, and stories noted from the beginning to the end of the book. My blog readers and Twitter followers will all be hearing about what I have learned from Douglas Waller’s “Lincoln’s Spies.” This book gave me understanding and value on my journey of learning about the Civil War. It filled many empty nooks and crannies of my Civil War knowledge.

Lincoln’s Spies focuses on four individuals who were Civil War spies: Allan Pinkerton, Elizabeth Van Lew, Lafayette Baker, and George Sharpe. Each of these spies lived a life of daring, intrigue, and excitement during a time of great change in the history of the United States of America. The stories of their lives intersect with the volatile story of the United States during the Civil War and Waller richly covers the people, times, and the events of the Civil War. Waller’s book is a deep well of Civil War information. I found his descriptions of the four main spies especially interesting.

Here are some brief looks at the four main spies of Lincoln’s Spies and a few book excerpts:

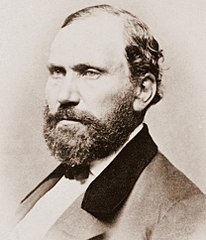

Allan Pinkerton

Allan Pinkerton was born in Scotland in 1819 and when he was ten-years-old his father died. Young Allan quit school but continued to read and study on his own, he learned to become a cooper to earn his living. He married and emigrated to the United States in 1842 where he built a cabin in Illinois. Pinkerton began a business working as a cooper in Illinois with wife Joan joining him there once the cabin was finished. Allan was an abolitionist and the Pinkerton’s cabin became a stop on the Underground Railroad.Pinkerton’s career in detective work and spying began serendipitously when he was walking in the woods one day looking for trees he could use to make barrel staves. Pinkerton came upon some counterfeiters in the woods who were busy at a fire hammering out fake coins. He watched them for a spell, and then he went to alert the sheriff. Pinkerton and the sheriff returned to stake out the counterfeiter’s campsite for the night. After their stakeout, the sheriff returned with a posse and arrested the counterfeiters who had a bag of fake dimes. This experience of luckily finding counterfeiters at work in the woods, spying on them, helping the sheriff with a stakeout, and then the subsequent arrest of the crooks led Pinkerton into a life of police, detective, and spy work.

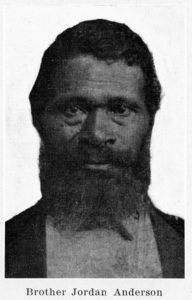

“Friends and associates believed Allan Pinkerton was gifted with courage and unusual powers of observation. As a young man he had been a labor agitator, falling under the spell of Scottish revolutionaries. He now hated slavery and had become a fanatical abolitionist. He thought his parents had been atheists and he considered himself one as well. He had honed a sixth sense to anticipate criminal activity before it happened. He was stubbornly persistent, refusing to be worn down by adversity. Yet he could be a tiresome prig, who harangued employees, friends, and relatives about the virtues of honesty, integrity, and courage. He was a tyrant at home, completely dominating his wife and children. He had dark, brooding eyes set deeply under a wide brow with a heavy beard that covered his face, save for his upper lip that he occasionally shaved. He was dour and humorless, only occasionally showing a sense of humor.”

– A description of Allan Pinkerton. Note that in the image of Pinkerton he has let the hair of his upper lip grow out.

Lincolns Spies, pages 3-4.

“We Never Sleep”

– Pinkerton used a business logo of a wide-open eye along with these words.

Lincolns Spies, page 12.

“Plums arrived here with Nuts this morning–all right.”

– A coded message Pinkerton sent after he helped Abraham Lincoln arrive safely in Washington, D.C. for his first inaugural despite death threats to Lincoln. Pinkerton was the “Plums” and Lincoln was the “Nuts.”

Lincolns Spies, page 19.

Elizabeth Van Lew

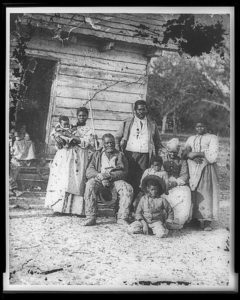

Elizabeth Van Lew was born in Richmond, Virginia in 1818 where her father John was very successful in a lucrative hardware business. Wealthy hardware man John Van Lew also owned slaves, despite this the Van Lew family supported abolition. Elizabeth’s maternal grandfather was Hilary Baker who was mayor of Philadelphia from 1796 to 1798. Baker was also an abolitionist, as was his granddaughter. The young Elizabeth studied at a Quaker school in Philadelphia where her anti-slavery sentiments grew stronger.When her father John died in 1843 Elizabeth and her abolitionist mother Eliza freed the Van Lew family’s slaves. The women paid some of them to continue working for them as servants. During the 1837-1844 depression Elizabeth used her $10,000 cash inheritance from her father to buy and set free some relatives of the slaves that she and her mother had freed. The Van Lew family would use their money to buy slaves and then set them free. Elizabeth Van Lew’s brother once went to Richmond’s slave market where he bought an entire enslaved family and then gave them all freedom so the family could remain together and not be separated under slavery.

With the start of the Civil War Elizabeth Van Lew and her mother began to care for wounded Union prisoners at Libby Prison in the Confederate capital of Richmond. Elizabeth took food and other supplies to the Yankee prisoners at Libby Prison to help make their captivity easier. She helped some escape by providing information about safe houses where they could find shelter during their escape. Elizabeth would gather information from the Yankee prisoners about Confederate troop strength and movements and then pass it on to Union commanders. Elizabeth Van Lew’s most important spy work began when she operated the “Richmond Underground,” a spy network that provided valuable information to Union army commanders. Her spy work was so useful that George Sharpe, the Army of the Potomac’s Intelligence Chief, said that Elizabeth’s spy efforts gave the army, “the greater portion of our intelligence in 1864-65.”

“Elizabeth Van Lew was a short woman, who had been quite fetching in her youth. But now in her forties and unmarried, she was considered by Richmond society to be an old maid. She loved her state, always speaking of Virginians in her soft southern accent as “our people”–although that love would be tested sorely in the years to come. She wore her dark blond hair always in tight curls that hung along her cheeks and neck. She had a thin, nervous-looking face with high cheekbones, pointed nose, and sparkling blue eyes that bore into anyone facing her stare. She was almost always attired in the antebellum style with black silk dress and bonnet whose ribbons tied under her chin in the front. She was clever to the point of “almost unearthly brilliance,” friends said, and decidedly feisty. She could be acid-tongued and scalding in her contempt for people whose social or political views clashed with her strong sense of right from wrong.”

– A description of Elizabeth Van Lew.

Lincolns Spies, page 30.

“She developed an early empathy for the slaves in her home and elsewhere. Their backbreaking work and the beatings she witnessed on city streets horrified her. On family vacations at western Virginia’s Hot Springs, a resort to escape the summer heat, she became friends with a slave trader’s daughter and was repelled by what she learned of the dreadful business.”

– Elizabeth Van Lew was an abolitionist.

Lincolns Spies, page 33.

“Slave power is arrogant, is jealous and intrusive, is cruel, is despotic, not only over the slave but over the community, the state”

– Elizabeth Van Lew

Lincolns Spies, page 33.

“Madness was upon the people!”

– Elizabeth Van Lew regarding Virginia seceding from the Union.

Lincolns Spies, page 36.

Learn Civil War History Podcast: Elizabeth Van Lew – A Union Spymaster in Richmond

Listen and learn about Elizabeth Van Lew.

Lafayette Baker

Lafayette Baker was born in New York in 1826. His family called him”Lafe” and he grew up to become a mechanic, he was good at repairing farm equipment. In 1853 Baker was in San Francisco after his younger brother urged him to come west like so many other young men to seek his fortune in the booming Gold Rush economy. Baker had no luck finding gold, he instead earned some money as a mechanic and as a saloon bouncer. In 1856 he joined the San Francisco Vigilance Committee, a very tough group of men.The San Francisco Vigilance Committee’s purpose was to control the climbing rate of lawlessness in San Fransisco caused by the huge amount of men of questionable character flooding into the city seeking their fortunes. Baker joined with hundreds of other committeemen who wore uniforms and carried swords as they worked for San Francisco. They were a tough crew, they took the law into their own hands, there were quick trials sometimes followed by equally quick hangings. Baker enjoyed the unlimited power and force of being a vigilante. He was good at this work.

The San Francisco Vigilance Committee eventually faded away and by 1861 Baker was in Washington, D.C. where he hoped to gain a job in President Abraham Lincoln’s new administration. Through some conniving, Baker met with General Winfield Scott. He started his spy career when Scott hired him, based on Baker’s California vigilante experience–which Baker exaggerated somewhat, to work as an espionage agent. Baker made a spy mission into Virginia, which had some mishaps, but he provided valuable information about Confederate troops in Virginia to General Scott. Scott then advanced Baker to the rank of captain. He served from September 1862 until November 1863 as the Provost Marshall of Washington, D.C. and administered the National Detective Bureau.

Reflecting back to his San Francisco vigilante days, Baker’s actions as a detective were questionable. He or his men literally used strong-arm tactics in their detective work. They gave little consideration or importance to obtaining warrants of those they chased after, or for their constitutional rights. After President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865 Baker’s men gathered the names of two of the conspirators, including the name of the assassin, John Wilkes Booth.

“Baker was a handsome man, with brown hair, a full red beard, and piercing gray eyes that were almost hypnotic. He stood five feet ten inches tall, a muscular 180 pounds, agile, almost catlike in his quick movements, always seemingly restless. H was a fine horseman, a crack shot. He did not swear or drink, priding himself on being a member of Sons of Temperance, a male brotherhood sworn against alcohol, which had started in New York City in 1842 and spread across the country. He was obsessed with Roman history. On his trip from California to New York, he devoured a book on a man who would become one of his role models: Eugéne Francois Vidocq, the famed and, Baker acknowledged, unsavory French detective who helped create France’s security police. Baker was as devious and manipulating as Vidocq, prone to lie about himself, with “the heart of a sneak thief,” according to one profile of him.”

– A description of Lafayette Baker.

Lincolns Spies, page 40.

“In 1856 he joined the 2,200 members of the San Francisco Vigilance Committee, each of whom was known only by his number. Baker’s was 208.”

– Lafayette Baker begins his work as a detective and spy.

Lincolns Spies, page 43.

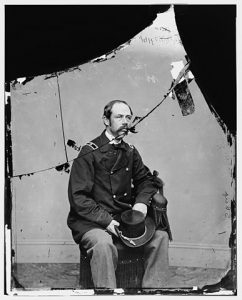

George Sharpe

George Sharpe was from Kingston, New York, a small town in Ulster County located on a bank of the Hudson River. The people of Kingston had strong anti-slavery beliefs and by 1855, sensing that conflict between North and South was coming, Kingston had six militia companies drilling and training in town. After Fort Sumter fell to the Confederates in April 1861 President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 state militiamen to volunteer for ninety days of service. They were needed to meet the challenge of the newly formed Confederacy and its fighting forces.In response to President Lincoln’s call, a meeting was held in Kingston where important men climbed on top of barrel-heads and gave rallying speeches to encourage young men to volunteer in the militia. Captain George Henry Sharpe of the 20th New York Militia, also known as the “Ulster Guard,” stood on top of a barrel and asked young men to come and serve with him in the militia. Soon Captain Sharpe had 248 men in his Company B which became part of the 20th New York Militia. This began George Sharpe’s Civil War journey, a journey in which he would continually advance in the army and one where he eventually became the country’s master spy. Sharpe became the Army of the Potomac’s Intelligence Chief and created an organization whose purpose was to learn and gather information about the Confederates.

“George Henry Sharpe was born on February 26, 1828. He was Henry and Helen’s only child. For some mysterious reason, the boy in later years attached an e to the end of his last name. Sharpe’s mother lived until age ninety, but throughout her life she was tormented by a nauseous stomach that left her constantly vomiting. She treated her attacks of biliousness with homeopathy, which she believed worked best. George never knew his father. Henry died in 1830 after suffering two paralytic strokes at an asylum in New York, just before his son turned two years old. Sharpe’s surrogate father–or at least the only father he felt he ever had–became Severyn Bruyn, a local banker who served as trustee of Henry Sharp’s considerable estate and doled out an allowance to George until he turned twenty-one and was allowed to control his own finances.”

– George Sharpe’s early life of family difficulties.

Lincolns Spies, pages 26-27.

“Sharpe’s superiors considered him a natural military leader, with a magnetic personality that made men want to follow him. He had a balding head, sad eyes, and a droopy mustache that gave him the look more of a city preacher than a combat commander. He was a learned man. I the breast pocket of his uniform coat he kept always a small, well-thumbed book of verses by his favorite poets, which he routinely read to his men. They never objected to his recitals.”

– A description of George Sharpe.

Lincolns Spies, page 25.

More Book Excerpts

Examples of the jewels of information included in Douglas Waller’s treasure chest of a Civil War book.

“Seventy-four-year-old Winfield Scott, a hero of the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War, was now in decrepit shape. Years of consuming rich foods had made “Old Fuss and Feathers” (his nickname because he enjoyed military pomp) so fat at 350 pounds, he could not walk even short distances and had to be hoisted onto a strong horse to review his troops. Scott found stairs so painful to climb because of the gout he suffered that Lincoln walked down from his second-floor White House office to confer with the general. Yet Scott’s mental acuity, as well as his ego, remained fit and trim.”

Lincolns Spies, page 45.

“Jefferson Davis was inaugurated for a six-year term on a rainy February 22 and moved his family into the old Brockenbrough mansion at Clay and 12th Streets, which became the Confederate White House. Haggard and worn looking, Davis was afflicted with neuralgia, digestive disorders, venereal disease, and bronchial problems and had lost sight in one eye. A workaholic who buried himself in paperwork and did not budget his time wisely, Davis was inaccessible, haughty, and peevish–not suffering fools lightly and feuding with his generals. A week after his inaugural, the Rebel president declared martial law in Richmond. He had reason to do so. Crime was becoming a problem in the refugee-swollen city. Not all the citizens of the capital of the Confederacy–indeed the entire Confederacy, Davis quickly realized–could be counted on to be loyal to the cause. Van Lew was one of them.”

Lincolns Spies, page 124.

“Sharpe checked his watch. It was shortly before 3 p.m. that day when he and other staff officers filed down the narrow center hall of the McClean house–one of those old-fashioned Virginia double homes perched on a knoll, he observed, with a large piazza that ran the full length of it–and turned to the left into a little parlor, bare save for a table and two or three chairs, Sharpe took a moment to sketch on a piece of paper where everyone stood or sat in the room. Grant and Lee sat at a table with their aides-de-camp beside them to take notes and reduce to writing terms of the surrender for the Army of Northern Virginia to the Army of the Potomac. Crowded in the opposite corner with Grant’s other aides, Sharpe craned his neck to see and hear what he said was “one of the most remarkable transactions of this nineteenth century.” Lee’s hair, he observed, “was white as driven snow. There was not a speck upon his coat; not a spot upon those gauntlets that he wore, which were as bright and fair as a lady’s glove.” Grant, by stark contrast, Sharpe believed, wore boots “nearly covered with mud; one button of his coat…had clearly gone astray.”

The two men struggled to make small talk–Grant apologizing for not wearing a sword as Lee did and asking what had become of the white horse the Rebel commander rode when they both served in Mexico. Lee responded with stiff bows, few words, and a “coldness of manner,” Sharpe recalled, that was “almost haughtiness.””

Lincolns Spies, page 394.

“After trying to swallow water and then whiskey from a glass, Booth attempted to speak but did so only in gasps and faint whispers. “Kill me,” he mumbled several times. He was paralyzed from the neck down. Conger put his ear close to Booth’s mouth to listen. “Tell mother I die for my country,” he heard the actor mutter. The two detectives could get him to say nothing of value.”

Lincolns Spies, page 410.

Author Douglas Waller

Douglas Waller lives in North Carolina and is an accomplished writer who has written best selling books including; Wild Bill Donovan: The Spymaster Who Created the OSS and Modern American Espionage, Disciples: The World War II Missions of the CIA Directors Who Fought for Wild Bill Donovan, and The Commandos: The Inside Story of America’s Secret Soldiers. Waller is a journalist who wrote about the CIA, Pentagon, State Department, White House, and Congress when he worked as a correspondent for the magazines Time and Newsweek.Book Information

Title: Lincoln’s Spies – Their Secret War To Save The UnionAuthor: Douglas Waller

Publisher: Simon & Schuster, August 6, 2019

Pages: 624

Book Dimensions: 6″ x 1.8″ x 9″

ISBN-13: 9781501126840

ISBN-10: 1501126849

Where to buy/order:

You can find Lincoln’s Spies at your local bookstore and online:

Simon & Schuster

Barnes & Noble

Books-A-Million

Indiebound.org

Editorial Reviews of Lincoln’s Spies

“[A] fast-paced, fact-rich account…Douglas Waller has most skillfully aimed a spotlight on this neglected aspect of the Union effort. Civil War military history can never again be read or told in quite the same way.” – The Wall Street Journal

“Douglas Waller’s fast-paced and deeply-researched narrative of Union intelligence operations in the Eastern theater of the Civil War cuts through the myths and fabrications that grew up around “Lincoln’s spies” and presents a professional, readable appraisal that emphasizes the positive contributions that Colonel George Sharpe and Richmond Unionist Elizabeth Van Lew made to ultimate Northern victory. This book is vital reading for anyone interested in the Civil War or in the origins of modern spycraft.”– James M. McPherson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era and The War That Forged a Nation.

“In Lincoln’s Spies, at long last, we have an absolutely compelling and essential account to stand alongside those on Lincoln’s generals, Lincoln’s admirals, and Lincoln’s cabinet secretaries. Here is a pantheon of heroes and a rogues’ gallery, the patriotic and the subversive, the idealistic and the crooked. Douglas Waller brings more than a keen intelligence to the early craft of intelligence. He is like a spy into the past who has uncovered some of the most incredible and devious characters of the Civil War and revealed their plots, schemes and secret worlds.” – Sidney Blumenthal, author of The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln series.

“Waller’s narrative moves chronologically, alternating between each of the four subjects and recounting their exploits in detail. This is a long but cracking good tale.”– Publishers Weekly

“A detailed, chronological look at the work of a handful of spies in President Abraham Lincoln’s network and the extent to which they helped defeat the Confederacy… A meticulous chronicle of all facets of Lincoln’s war effort.” – Kirkus Reviews