A Sixty-Nine-Year-Old Gettysburg Civilian Joins the Battle

John Burns – The Old Hero of Gettysburg

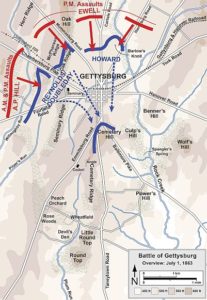

Robert E. Lee and his invading Army of Northern Virginia brought the Civil War to the quiet and pastoral town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in early July 1863. A gutsy Gettysburg civilian named John Lawrence Burns who was a cobbler, a town constable, and an old man, took part in the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Civilian Burns is known as, “The Old Hero of Gettysburg.”

There is truth and myth concerning the story of John Burns. Over time, his story has become somewhat confusing. Burns or others seemed to add to it, or change it, as time went by, usually by embellishing Burns’ story. Whether this was intentional or not, who can say?

It can be difficult historically to separate fact from fiction regarding John Burns. Let’s recognize that and enjoy the story of “The Old Hero of Gettysburg.”

John Burns was born in Burlington, New Jersey on September 5, 1793. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, and he claimed to have fought at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane or the Battle of Niagara Falls on July 25, 1814. Burns told the story that he fought in the battle and said what regiment he was in, and the name of his commander.A problem with Burns’ Lundy’s Lane claim is that both the regiment and the commander Burns’ named were not at the battle. In the War of 1812, John Burns served in a unit near Philadelphia, but he saw no action.

There are stories about John Burns fighting in, or attempting to fight in, the Seminole War and volunteering to fight in the Mexican War, but these are nothing but tall tales. There are no records to back up that Burns served in these two wars.

Records confirm that early in the Civil War John Burns was a teamster in the Frederick and Hagerstown vicinity as his name appears on a list of civilian contractors. He was close enough to possibly hear the sounds of the Battle of Falling Waters, but he did not participate in the fighting there as he claimed he did. There is nothing to prove that John Burns had involvement in any Civil War military action at any time, before July 1, 1863.

John Burns at The Battle of Gettysburg On July 1, 1863

- At approximately 8:00 in the morning of July 1, 1863, sixty-nine-year-old John Burns leaves his home and argues with neighbors that they should be fighting the Confederates who are now coming to Gettysburg. However, the citizens of Gettysburg preferred to hide safely in their cellars during the battle. Burns then moves toward the fighting.

- Burns spends most of the morning in the vicinity of the Lutheran Seminary, but he is not involved in any fighting.

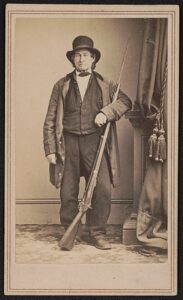

- Next, he goes back to Gettysburg and obtains a musket, then he heads back to the field. It has been told and supposed the musket was Burns’ musket from the War of 1812.

- Around noon, Burns encounters the 150th Pennsylvania, the Bucktails, near the McPherson Farm. The men are amused that an old man wants to join them and fight. Burns meets up with an infantry officer and asks to be allowed to join in with the officer’s regiment. The officer sends Burns over to the regiment’s commander, Colonel Langhorne Wister.

- Wister directs Burns over to the McPherson Farm. He hopes the old man might be safe there in the surrounding woods from enemy bullets. Unfortunately for Burns, Wister had unwittingly sent him to a place that instead turned out to be a hot spot of fighting. Somewhere in all this, Burns probably obtains a more modern musket.

There is confusion about what weapon John Burns had at various times on July 1st at the Battle of Gettysburg. Some say he used his flintlock musket from the War of 1812, others say he obtained a more modern musket or muskets, during the fighting. Perhaps Burns used several different weapons that morning. All depending upon opportunity.

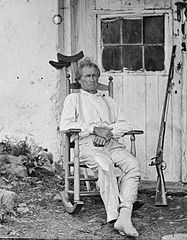

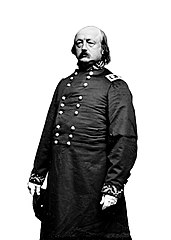

Mathew Brady took a picture of John Burns after the Battle of Gettysburg which shows Burns sitting in a rocking chair with a flintlock musket nearby. The weapon is supposedly Burns’ War of 1812 musket. It could be, or it might only be a prop for the photograph with no other significance.- Burns joins up with the 7th Wisconsin, part of the Iron Brigade, at the edge of the Herbst Woods, also known as the McPherson Woods or Reynolds Woods, around 1:00 in the afternoon. Heavy fighting begins and John Burns takes cover behind a tree and participates in the battle.

- Old man John Burns was brave and not overly concerned about his safety. He fought along with the 7th Wisconsin Infantry and the 24th Michigan. He did not run. He fired his weapon at the Confederates. A story claims he picked off a Rebel officer who was charging forward on his horse. This continues to be part of John Burns’ story, but it may only be conjecture.

- At 4:00 in the afternoon the Yankees must make a retreat. During the retreat, Burns is wounded in an ankle. The ankle wound takes him to the ground and Burns is unable to walk. He may have been wounded more times, but here too there is uncertainty. How many times Burns was wounded varies depending on who you read or listen to. We do know he was wounded in an ankle.

- Burns will lie on the field until the next morning. As a non-uniformed combatant, he could be shot or hanged by the Confederates. He moved away from his weapon, or tossed it away, and hid his ammunition by burying it underneath him.

- Eventually, the Johnny Rebs found Burns. He told them he was a civilian on the battlefield because he was looking to find a doctor for his ill wife. Or… the story also goes he said he was looking for a missing cow and was wounded when he became mixed up in crossfire. The Johnny Rebs were skeptical of Burns’ story, but they decided not to shoot or hang the old man.

- During the night of July first or early the next morning, John Burns either crawls or is carried somehow to a home on Seminary Ridge. The home belongs to Alexander Riggs, a friend of his, so Burns was familiar with the house and its surroundings. Later, Burns is found lying on top of Riggs’ cellar door.

- On the afternoon of July second, John Burns is taken by wagon to his home on Chambersburg Street. When Burns is back home, and his wife sees he is wounded, she remarks that she told him not to get into the fight. Nevertheless, Burns recovers from his battle wound or wounds.

Controversy Surrounding John Burns

Burns was not always a popular person in Gettysburg. He had a habit of gossiping and of spreading rumors. When John Burns was constable of Gettysburg, one of his duties was to make a report every three months of his work. This report would include his duties regarding matters such as; the serving of summons, deer that were killed out of season, repairs to street name signs, and the serving of alcohol over a certain amount.

He was also to list in his report any illegitimate children born during the three months. In one of these reports, John Burns writes, “One Martha Gilbert Gave Birth To A Bastard Child.” This is curious because John Burns and his wife were childless, but Martha Gilbert was their adopted daughter.

Some in Gettysburg made the accusation that Burns was the father of Martha Gilbert’s child born out of wedlock. This was speculation, but the Gettysburg people were now in turn spreading gossip and rumors about John Burns.

The Old Hero of Gettysburg Meets President Abraham Lincoln

On August 22nd, 1863, a woodcut of Mathew Brady’s photograph of John Burns sitting in a rocking chair with crutches and a flintlock rifle nearby, appeared on the cover of the highly circulated Harper’s Weekly magazine. Word spreads across the country about old John Lawrence Burns, the War of 1812 veteran who fought at Gettysburg.

John Burns became famous throughout the United States as, “The Old Hero of Gettysburg.” President Abraham Lincoln heard about John Burns and when he came to Gettysburg to deliver his Gettysburg Address on November 19th, 1863, he wanted to meet him. Lincoln and Burns meet after the speech and shake hands, with nearby reporters observing it all. Their reporting of the meeting brings even more celebrity and fame to John Burns.Lincoln walked with John Burns from the David Wills house to the Presbyterian Church. At the church, Lincoln and Burns sat together during a political rally. In 1864, both houses of Congress passed a bill giving John Burns the right to a pension. At the White House on February 2, 1864, President Lincoln signed the bill into law with John Burns present.

The Old Hero of Gettysburg – Patriot

John Burns died on February 4th, 1872, of pneumonia. He is buried next to his wife in the Evergreen Cemetery at Gettysburg. John Burns’ gravestone is inscribed with the word “Patriot.” At his grave, the American flag flies twenty-four hours a day to honor the Old Hero of Gettysburg.

Only one other American flag flies twenty-four hours a day at Evergreen Cemetery. That flag flies for Jennie Wade who was the only civilian killed during the Battle of Gettysburg. If you visit the Gettysburg National Military Park you will find a monument to John Burns at McPherson’s Ridge.