Traveller – Robert E. Lee’s Horse

Traveller was General Robert E. Lee’s horse during most of the Civil War and afterwards too. Traveller is the famous “Confederate grey” colored horse so well recognized in Civil War photographs and art.

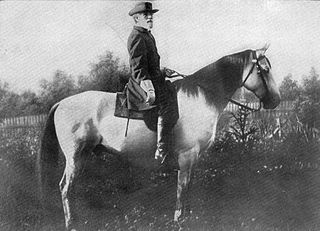

General Robert E. Lee and Traveler

General Robert E. Lee and Traveller were together almost the entire Civil War. Lee rode Traveller to Appomattox Court House when he surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865. After the Civil War, while Lee was president of Washington University (later renamed to Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, Traveller was with Lee.

At Washington University, Lee still enjoyed riding Traveller and he often took Traveller for rides in and around Lexington. Robert E. Lee is interred in a crypt beneath the Lee Chapel on the campus of Washington and Lee University. Traveller is buried just outside the Lee Chapel, showing how important the horse was to Lee.

What Was Traveller Like?

Many have wondered what this magnificent grey horse, a horse General Robert E. Lee was so very fond of, was like in life.

Perhaps Captain Robert E. Lee (General Lee’s son) and General Robert E. Lee’s own words are our best source of information about Traveller. The below book excerpts are from Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee by Captain Robert E. Lee, His Son, and are from the year 1862:

“The General was on the point of moving his headquarters down to Fredericksburg, some of the army having already gone forward to that city. I think the camp was struck the day after I arrived, and as the General’s hands were not yet entirely well, he allowed me, as a great favour, to ride his horse “Traveller.” Amongst the soldiers this horse was as well known as was his master. He was a handsome iron-gray with black points–mane and tail very dark–sixteen hands high, and five years old. He was born near the White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, and attracted the notice of my father when he was in that part of the State in 1861. He was never known to tire, and, though quiet and sensible in general and afraid of nothing, yet if not regularly exercised, he fretted a good deal especially in a crowd of horses. But there can be no better description of this famous horse than the one given by his master. It was dictated to his daughter Agnes at Lexington, Virginia, after the war, in response to some artist who had asked for a description, and was corrected in his own handwriting:”

“If I were an artist like you I would draw a true picture of Traveller–representing his fine proportions, muscular figure, deep chest and short back, strong haunches, flat legs, small head, broad forehead, delicate ears, quick eye, small feet, and black mane and tail. Such a picture would inspire a poet, whose genius could then depict his worth and describe his endurance of toil, hunger, thirst, heat, cold, and the dangers and sufferings through which he passed. He could dilate upon his sagacity and affection, and his invariable response to every wish of his rider. He might even imagine his thoughts, through the long night marches and days of battle through which he has passed. But I am no artist; I can only say he is a Confederate gray. I purchased him in the mountains of Virginia in the autumn of 1861, and he has been my patient follower ever since–to Georgia, the Carolinas, and back to Virginia. He carried me through the Seven Days battle around Richmond, the second Manassas, at Sharpsburg, Fredericksburg, the last day at Chancellorsville, to Pennsylvania, at Gettysburg, and back to the Rappahannock. From the commencement of the campaign in 1864 at Orange, till its close around Petersburg, the saddle was scarcely off his back, as he passed through the fire of the Wilderness, Spottsylvania, Cold Harbour, and across the James River. He was almost in daily requisition in the winter of 1864-65 on the long line of defenses from Chickahominy, north of Richmond, to Hatcher’s Run, south of the Appomattox. In the campaign of 1865, he bore me from Petersburg to the final days at Appomattox Court House. You must know the comfort he is to me in my present retirement. He is well supplied with equipments. Two sets have been sent to him from England, one from the ladies of Baltimore, and one was made for him in Richmond; but I think his favourite is the American saddle from St. Louis. Of all his companions in toil, ’Richmond,’ ’Brown Roan,’ ’Ajax,’ and quiet ’Lucy Long,’ he is the only one that retained his vigour. The first two expired under their onerous burden, and the last two failed. You can, I am sure, from what I have said, paint his portrait.”

There can be little doubt that Traveller was just as an extraordinary horse, as Robert E. Lee was a general!

Traveller Causes Injuries To Lee’s Hands

As fond as Robert E. Lee was of Traveller, Lee did not completely escape the hazards and risks of an equestrian. The following excerpt (also from 1862) describes how Traveller was once responsible for injuring General Lee’s hands (as was alluded to in the above excerpts.) Captain Robert E. Lee writes:

“He was much on foot during this part of the campaign, and moved about either in an ambulance or on horseback, with a courier leading his horse. The accident which temporarily disabled him happened before he left Virginia. He had dismounted, and was sitting on a fallen log, with the bridle reins hung over his arm. Traveller, becoming frightened at something, suddenly dashed away, threw him violently to the ground, spraining both hands and breaking a small bone in one of them. A letter written some weeks afterward to my mother alludes to this meeting with his son, and to the condition of his hands:”

“…I have not laid eyes on Rob since I saw him in the battle of Sharpsburg–going in with a single gun of his for the second time, after his company had been withdrawn in consequence of three of its guns having been disabled. Custis has seen him and says he is very well, and apparently happy and content. My hands are improving slowly, and, with my left hand, I am able to dress and undress myself, which is a great comfort. My right is becoming of some assistance, too, though it is still swollen and sometimes painful. The bandages have been removed. I am now able to sign my name. It has been six weeks to-day since I was injured, and I have at last discarded the sling.”