The Thirteenth Amendment To The Constitution Abolished Slavery In The United States.

December 18, 1865

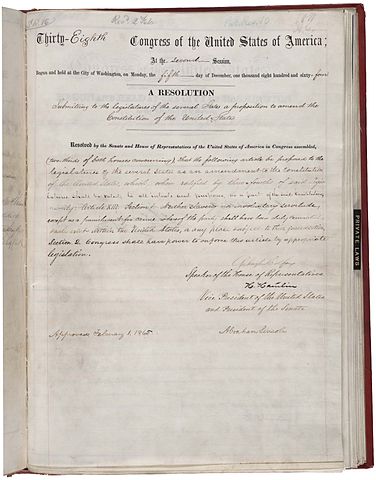

The Senate had passed an amendment abolishing slavery on April 8, 1864, but the House defeated it in June, 1864. The House then passed the Thirteenth Amendment on January 31, 1865. The next day, President Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress and submitted this potential amendment to the state legislatures for ratification.By December 18, 1865 the states had ratified the Thirteenth Amendment and it was proclaimed in effect. That was a good day.

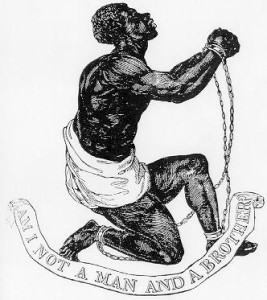

“Hello, Massa; bottom rail on top dis time.”

…An African-American Union soldier spoke these words to his former master, who was now a prisoner.

Worth noting:

- On April 9, 1865 General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia thus ending the Civil War.

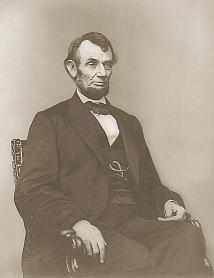

- President Lincoln had issued his Emancipation Proclamation On January 1, 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation declared free the slaves in the parts of the country which were in rebellion. Lincoln’s proclamation contained the words, ”all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; . . ..” The Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to the states which had remained in the Union.

- President Abraham Lincoln did not live to see the Thirteenth Amendment, with its abolishment of slavery, become part of the Constitution.

The Thirteenth Amendment To The Constitution

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a

punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted,

shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their

jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by

appropriate legislation.

Learn Civil War History Podcast Episode Seven: Freedman Jourdon Anderson Writes A Letter To His Old Master

Spotify