Mules Are Sturdy, Hardy, And Durable Animals

Mules in the Civil War provided a lot of brute muscle to get the tough, backbreaking work done for both the North and the South. Their specialty was pulling wagons. It’s worth noting that a mule is a cross between a male donkey and a female horse. Mules are sterile and cannot reproduce, although there are exceptions. A hinny is the result of crossing a male horse with a female donkey. Mules are easier to produce.

In the 1800s United States, mules were very commonly used on the many farms of the country’s agricultural based society. Mules are sturdy, hearty, and durable, they can perform hard work under severe conditions that might injure or kill a horse. They can survive on the poorest of food. Before America become mechanized, the mule was a much needed draft animal.

At the start of the Civil War it is estimated there were more than a million mules in the country, and most of them were found in the South. The states producing the most mules were Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee. Kentucky in particular, was known for having the best quality and largest size of mules.

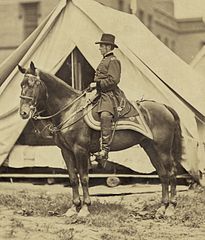

During the Civil War, mules would often be used to pull wagons full of supplies, forage, or ammunition. Mules would be worked in teams of six and hitched to a wagon in tandem. The mule driver would ride on the back of the mule nearest to the wagon and on the right side. The mule driver kept his authority over the mules, no small task as mules are often very uncooperative, with a whip called a “black snake.” The black snake would be cracked near or on the ears of a mule to gain its attention and cooperation.

The mule driver was often an expert at using oaths and streams of profanity to communicate his desires to his mules. A good mule driver was very valuable, as he would know all the tricks needed to get his mules to obey. Mule drivers had to be as tough as their mules. Mules were also used as pack animals, beasts of burden, and would carry regimental baggage, rations, and boxes of small arms ammunition with specially designed pack saddles strapped on their backs.

Mules Are Not Like Horses

Mules are not as workable and as cooperative as horses (As an aside, your BlogMaster has dealt with some very mean and nasty horses in his day, and finds it very scary to think that a mule could be worse than a bad horse!) and are known for having their own mind. Mules have the astonishing ability to kick very forcefully, accurately, and effectively. Mules were very nervous and skittish under the fire of a battlefield and could not be used for cavalry, artillery, or ambulance corps work. Mules could not be trusted with this work. Horses were used for these duties in the Civil War because they were more cooperative and easier to work with than mules.

Pulling supply wagons and working as a pack animal, is what mules were best at. Mules were used to get ammunition as close to the front lines of a battle as possible, but there was a limit as to how close, because they could not be trusted. It was just too dangerous to get mules too close to battle. Under battle fire, mules would probably become uncontrollable, would panic, and might even bolt towards enemy lines!

John D. Billings served in the Army of the Potomac. In his 1888 book Hard Tack and Coffee, he has a chapter devoted to the army mule. Billings’ words best describe what Civil War mules, and working with them, was like. Below are some chosen informative and entertaining excerpts about mules from Hard Tack and Coffee by John D. Billings:

Advantages of Mules

“Aside from this nervousness under fire, mules have a great advantage over horses in being better able to stand hard usage, bad feed, or no feed, and neglect generally. They can travel over rough ground unharmed where horses would be lamed or injured in some way. They will eat brush, and not be very hungry to do it, either. When forage was short, the drivers were wont to cut branches and throw before them for their refreshment. One m.d. (mule driver) tells of having his army overcoat partly eaten by one of his team — actually chewed and swallowed. The operation made the driver blue, if the diet did not thus affect the mule.”

Six-Mule Team

“In organizing a six-mule team, a large pair of heavy animals were selected for the pole, a smaller size for the swing, and a still smaller pair for leaders. There were advantages in this arrangement; in the first place, in going through a miry spot the small leaders soon place themselves, by their quick movements, on firm footing, where they can take hold and pull the pole mules out of the wallow. Again, with a good heavy steady pair of wheel mules, the driver can restrain the smaller ones that are more apt to be frisky and reckless at times, and, assisted by the brake, hold back his loaded wagon in descending a hill. Then, there was more elasticity in such a team when well trained, and a good driver could handle them more gracefully and dexterously than he could the same number of horses.”

Mule Driver and Mule Driving

“It was really wonderful to see some of the experts drive these teams. The driver rides near the pole mule, holding in his left hand a single rein. This connects with the bits of the near lead mule. By pulling this rein, of course the brutes would go to the left. To direct them to the right one or more short jerks of it were given, accompanied by a sort of gibberish which the mule drivers acquired in the business. The bits of the lead mules being connected by an iron bar, whatever movement was made by the near one directed the movements of the off one. The pole mules were controlled by short reins which hung over their necks. The driver carried in his right hand his black snake, that is, his black leather whip, which was used with much effect on occasion.”

The Black Snake

“[…] I have referred to the Black Snake. It was the badge of authority with which the mule-driver enforced his orders. It was the panacea for all the ills to which mule-flesh was heir. It was a common sight to see a six-mule team, when left to itself, get into an entanglement, seemingly inextricably mixed, unless it was unharnessed; but the appearance of the driver with his black wand would change the scene as if by magic. As the heel-cord of Achilles was his only vulnerable part, so the ears of the mule seemed to be the development through which his reasoning faculties could be the most quickly and surely reached, and one or two cracks of the whip on or near these little monuments, accompanied by the driver’s very expressive ejaculation in the mule tongue, which I can only describe as a kind of cross between an unearthly screech and a groan, had the effect to disentangle them unaided, and make them stand as if at a “present” to their master. When off duty in camp, they were usually hitched to the pole of their wagon, three on either side, and here, between meals, they were often as antic as kittens or puppies at play, leaping from one side of the pole to the other, lying down, tumbling over, and biting each other, until perhaps all six would be an apparently confused heap of mule. If the driver appeared at such a crisis with his black “ear-trumpet,” one second was long enough to dissolve the pile into its original mule atoms, and arrange them again on either side of the pole, looking as orderly and innocent as if on inspection.”

Unexpected, Instantaneous Mule Kicks

“I have stated that the mule was uncertain; I mean as to his intentions. He cannot be trusted even when appearing honest and affectionate. His reputation as a kicker is worldwide. He was the Mugwump of the service. The mule that will not kick is a curiosity. A veteran relates how, after the battle of Antietam, he saw a colored mule-driver approach his mules that were standing unhitched from the wagons, when, presto! one of them knocked him to the ground in a twinkling with one of those unexpected instantaneous kicks, for which the mule is peerless. Slowly picking himself up, the negro walked deliberately to his wagon, took out a long stake the size of his arm, returned with the same moderate pace to his muleship, dealt him a stunning blow on the head with the stake, which felled him to the ground. The stake was returned with the same deliberation. The mule lay quiet for a moment, then arose, shook his head, a truce was declared, and driver and mule were at peace and understood each other.”

All of the above quoted mule excerpts are from Hard Tack and Coffee by John D. Billings.

Twenty Mule Team pulling 100 year old wagons.

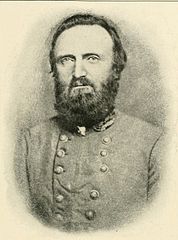

Jeff Davis rode a dapple gray,

Lincoln rode a mule,

Jeff Davis is a gentleman,

And Lincoln is a fool.

— A verse from a Confederate song.

“If you don’t have my army supplied, and keep it supplied, we’ll eat your mules up, sir.”

— William Tecumseh Sherman’s warning to an army quartermaster before the departure of Sherman’s army from Chattanooga toward Atlanta.

Learn Civil War History Podcast: Mules In The Civil War

Spotify