War is Hell…

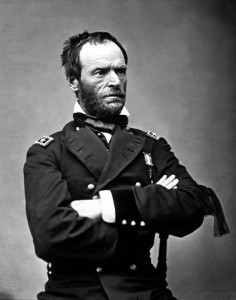

Facts and Notes About General William Tecumseh Sherman

- William Tecumseh Sherman was born in Lancaster, Ohio on February 8, 1820. Sherman’s middle name of “Tecumseh” was given to him at birth. The name “Tecumseh” was from a great Shawnee Indian leader and warrior who had almost defeated the United States Army.

- Sherman graduated sixth in his class of 1840 at West Point. He was highly intelligent, aggressive, and had a good imagination. These characteristics would help to make Sherman one of the great Union generals of the Civil War.

- When the Civil War broke out, Sherman was the superintendent of a military academy in Louisiana called the Alexandria Military Institute. This military academy would become the foundation of Louisiana State University.* Sherman was a West Point graduate, age 41, and a civilian when the Civil War started. He volunteered for service. Sherman took command of a brigade and led it at the Battle of First Bull Run. Sherman was lean, grizzled, and had red hair, he did not much care about his personal appearance.

- The Battle of Shiloh was fought on April 6, and 7, 1862. On the first day of battle, troops led by General Sherman came under heavy fire. Despite efforts by Sherman to rally the men, the Union troops (who were new to battle) fled to the rear. That evening, Confederates were camped on ground that in the morning had belonged to Union troops. Confederate General Beauregard spent the night sleeping in Sherman’s bed. The next day, April 7, Grant renewed the fight and pushed the Rebel troops back to their original attack position. The Billy Yanks had their camp again. Perhaps on the night of April 7, General Sherman got his bed back from General Beauregard.

- Benjamin Harrison was from Ohio and saw action in the Western Theater during the Civil War. He served in Sherman’s Army during the March to the Sea. In 1888, he became president of the United States of America.

- On May 4, 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman begins his march to Atlanta, Georgia. His army numbered 110,000 men. Sherman’s March to the Sea will make history, and make him hated in the South.

- In 1864, when Sherman was making his way through the South, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston won a victory at Kennesaw Mountain. At the end of the Civil War, Johnston was in command in the Carolinas. Johnson staged a defensive campaign after Lee surrendered to Grant on April 9, 1865. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston finally surrendered to General Sherman at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865. After the war, Sherman and Johnston became friends.

- William Tecumseh Sherman died of pneumonia in New York City on February 14, 1891. Sherman and Joseph E. Johnston (Sherman’s old Confederate adversary) had reconciled in the years since the Civil War. Johnston served as an honorary pall bearer at Sherman’s funeral on a rainy and cold day. During the funeral, Johnston removed his hat in the cold rain as other mourners did the same. He was urged to put the hat back on so he would avoid the wet and cold. Johnston said: “If I were in his place and he standing here in mine he would not put on his hat.” Former Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston developed pneumonia from the rain and cold at Sherman’s funeral. Johnston died only a few weeks later.

- In Washington, D.C., there is a small park at Fifteenth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue. At this park there is a statue of Union General William Tecumseh Sherman. This statue is forty-three feet high and depicts Sherman on a horse during a march. On the granite base of this statue is a Sherman quote in which he states his idea of what the purpose of war is: “War’s Legitimate Object Is More Perfect Peace.”

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!