For both Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs, a common food was hardtack. Hardtack was a roughly three-inch by three-inch square and quarter-inch thick cracker or biscuit baked from unleavened flour, water, and salt. It was inexpensive and durable, qualities making it suitable for military campaigning.

Although hardtack was often a source of energy and sustenance during the Civil War, it usually was a target of scorn for the soldiers. Here on August 1, 1863 Sergeant Lawrence Van Alstyne, of the 128th New York Infantry U.S.A., describes hardtack in an entry from his diary:

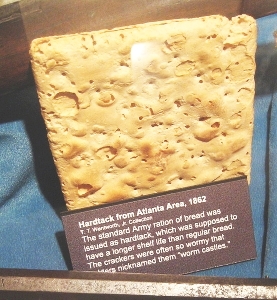

Preserved hardtack from U.S. Civil War, Wentworth Museum, Pensacola, Florida.“A year ago to-day I cradled rye for Theron Wilson, and I remember we had chicken pie for dinner with home-made beer to wash it down, To-day I have hard-tack. Have I ever described hard-tack to you? … In size they are about like a common soda cracker, and in thickness about like two of them…. But… The cracker eats easy, almost melts in the mouth, while hard-tack is harder and tougher than so much wood. I don’t know what the word “tack” means, but the “hard” I have long understood….. Very often they are mouldy, and most always wormy. We knock them together and jar out the worms, and the mould we cut or scrape off. Sometimes we soak them until soft and then fry them in pork grease, but generally we smash them up in pieces and grind away until either the teeth or the hard-tack gives up. I know why Dr. Cole examined our teeth so carefully when we passed through the medical mill at Hudson.”

Photo by Infrogmation, Infrogmation of New Orleans

The caption of the hardtack picture reads:

Hardtack from Atlanta area, 1862.

T.T. Wentworth, Jr. Collection

The standard Army ration of bread was issued as hardtack, which was supposed to have a longer shelf life than regular bread. The crackers were often so wormy that soldiers nicknamed them “wormcastles.”

John D. Billings Of The Army of the Potomac Describes Hardtack

“I will speak of the rations more in detail, beginning with the hard bread, or, to use the name by which it was known in the Army of the Potomac, Hardtack. What was hardtack? It was a plain flour and water biscuit. Two which I have in my possession as mementos measure three and one-eighth by two and seven-eighths inches, and are nearly half an inch thick. Although these biscuits were furnished to organizations by weight, they were dealt out to the men by number, nine constituting a ration in some regiments, and ten in others; but there were usually enough for those who wanted more, as some men would not draw them. While hardtack was nutritious, yet a hungry man could eat his ten in a short time and still be hungry. When they were poor and fit objects for the soldiers’ wrath, it was due to one of three conditions: First, they may have been so hard that they could not be bitten; it then required a very strong blow of the fist to break them. The cause of this hardness it would be difficult for one not an expert to determine. This variety certainly well deserved their name. They could not be soaked soft, but after a time took on the elasticity of gutta-percha.

“The second condition was when they were mouldy or wet, as sometimes happened, and should not have been given to the soldiers. I think this condition was often due to their having been boxed up too soon after baking. It certainly was frequently due to exposure to the weather. It was no uncommon sight to see thousands of boxes of hard bread piled up at some railway station or other place used as a base of supplies, where they only imperfectly sheltered from the weather, and too often not sheltered at all. The failure of inspectors to do their full duty was one reason that so many of this sort reached the rank and file of the service.

“The third condition was when from storage they had become infested with maggots and weevils. These weevils were, in my experience, more abundant than the maggots. They were a little, slim, brown bug an eighth of an inch in length, and were great bores on a small scale, having the ability to completely riddle the hardtack. I believe they never interfered with the hardest variety.”

“But hardtack was not so bad an article of food, even when traversed by insects, as may be supposed. Eaten in the dark, no one could tell the difference between it and hardtack that was untenanted. It was no uncommon occurrence for a man to find the surface of his pot of coffee swimming with weevils, after breaking up hardtack in it, which had come out of the fragments only to drown; but they were easily skimmed off, and left no distinctive flavor behind. If a soldier cared to do so, he could expel the weevils by heating the bread at the fire. The maggots did not budge in that way.”

…John D. Billings was a soldier in the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War. These quotes are from his book, Hardtack and Coffee – A Soldier’s Life In The Civil War, where he describes hardtack and its common problems.

Here is a post with a recipe for hardtack. Try it, you might like it!

Hardtack, Weevils and Other Enemies

by Jim Surkamp

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!