Author Brendan J. Lyons, the Boy Scouts of America, and Charles “Charley” Edwin King

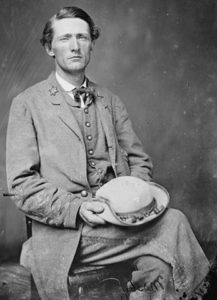

As a young man, Charley author Brendan J. Lyons of West Chester, Pennsylvania was a Boy Scout. He’d earned the rank of Life and began working on earning the Eagle rank, the highest and most prestigious rank in Scouting. The Eagle rank requires the Scout to complete a community service project and Lyons needed to find just such a project. These projects are not always easy to find. Lyon’s interest in history helped him to find his community service project.

Lyons learned from his scout leader, who was a member of the Sons of Union Veterans, about Charley King, he was a twelve-year-old drummer boy from West Chester who went off to fight and die in the Civil War.

Charley King’s story intrigued Lyons, especially the part about how no one knew for sure where the young Civil War drummer boy was buried. For his Eagle Scout community service project, Lyons decided he would raise money (along with help from the Sons of Union Veterans and others who had an interest in history) for a monument to honor Charley King that would be placed in the Green Mount Cemetery, where members of the King family are buried.

Brendan J. Lyons completed his Eagle Scout community service project and earned the rank of Eagle. But for many years afterward, Lyons now an adult, felt like his work with Charley King was incomplete.

Lyons wanted to tell the story of the Civil War drummer boy. The trouble was, there was that not much known of Charley’s actual history. After all, Charley died when he was only thirteen years old, he did not have the chance to make much life history. What is known is the factual history of Company F of the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteers, the company in which Charley King served. Brendan J. Lyons began researching and writing.

Charley is a novel that combines historical fact and creative fiction to tell a story as accurately as possible about Charley King. It’s a convincing effort. Lyons’ Eagle Scout community service project became one of his life’s works with his book: Charley – The True Story of the Youngest Soldier to Die in the American Civil War.

Charley King’s Early Life Before the Civil War

I have chosen some excerpts from Charley to introduce you to Lyons’ story about Charley King and how the young lad became a drummer in the Civil War. Included too, I have added some explanatory comments of my own. Note that April 3, 1861, was a Wednesday.

My Comments:

- Charles “Charley” Edwin King was born on April 3, 1849.

- Charley died on September 20, 1862.

- Charley’s father was Pennell, he was a tailor.

- His mother’s name was Adaline.

- His brother Lewis, was two years younger than Charley.

“On this Wednesday in April, one month after the inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln, the nation stood on the brink of conflict.”

“On this Wednesday in April, as the country was coming apart at the seams because of the growing tide of secession, unprecedented animosity divided the nation that first brought the concepts of free and equal representation to the world.”

“On this Wednesday in April 1861, Charley King was turning twelve years old.”

“At this time, when America faced its greatest test since the very revolution that created it, Charley had reached the age that – by his judgment – qualified him to stand and fight for his nation. Whether his father would agree remained to be seen, but in Charley’s mind, he could lift a rifle as well as anyone and his home needed stout defenders.”

Young Charley King Is a Drummer

“Charley could see himself quite easily, decked in Union blue and marching beside his countrymen. He was already accomplished at keeping time, by virtue of his skill on the drum. His father often claimed Charley had been drumming perfect military cadence since before he could walk. Whether or not that was true, Charley couldn’t say, but he certainly loved to play his drum.”

“Apparently, he loved to play it a tad too much and had just recently drummed right through the head of his snare. It happened two weeks earlier and since then, he’d had to make do with whatever he could get away with drumming on.”

“With the drum beat in his mind, however, he was able to mark time perfectly around his room and, as he did. Envision a future where his deeds brought glory to his family and his nation. One day–and Charley felt that day would come soon–he would find himself marching into Richmond alongside his fellow Union soldiers as streams of confetti and other colorful paper rained down on them. They would be celebrated as liberators from the wicked grasp of traitors and the people would love them for it.”

“The celebration would be even greater when he returned home a hero. His parents would hug him tight and say how proud they were of him. All of West Chester would come out to celebrate. Perhaps all of Chester County!”

“Now boy, I must say–eleven, twelve, or even fifteen, I think it not wise for you to wish to go to war. Truthfully, I will not allow it. Your passion is commendable, but it would be far too dangerous. You are much too young, and besides quite slight for your age. I think you are perhaps the smallest boy in your class. Charley you cannot go to war.”

My Comments:

Charley was caught up in enthusiasm about going off to war and to “See the Elephant,” which means to experience battle. However, his wise father was against young Charley going off to war.

Charley Gets a New and Special Drum On His Birthday

“By the time the day’s ends came, Charley could barely keep his feet from tapping. He was prepared to leap out of his chair and sprint home to see what news may have come while lessons were being taught, but he was stopped by a group of friends before he could.

“‘Where are you headed Charley?’ one of them asked.

“‘Oh, just going home. I thought I’d stop by the telegraph office and see if there was any war news on the way.’

“‘Are you marching down?’ asked another.

“‘I… guess I can…’ Charley wasn’t sure where this line of questions was going. The other kids were his friends, but they rarely showed interest in his marching about anymore. It was odd that they would ask him now.

“‘Why don’t you lead us?’ The first classmate asked. ‘We figured if the war is gonna happen maybe we ought to get the top shape, right?’

“Charley frowned.

“‘I guess only I can’t really lead you guys. My drum is broken.’

“‘Well, I guess you’ll need a new drum!’ A voice behind him made Charley jump.

“Charley whirled around to see his parents standing there side by side, huge smiles on their faces. His father held out a large cylindrical package.

“‘Happy birthday, Charley,’ he said.

“‘We hope you like it,’ his mother added.

“Without hesitating, Charley took the package and tore off the paper. Inside, was a large blue snare drum with red trim on the top and bottom. Around the middle, it was emblazoned with a soaring bald eagle on opposite sides of the drum.

“‘This is amazing,’ Charley gasped. ‘It’s perfect… the eagle, is this…?’

“‘The very drum that the musicians in the Army of the Potomac play,’ Pennell confirmed.

“‘Your father had the Sweney boy send one in,’ Adeline said. ‘He made such a show about having all that extra work so you wouldn’t think anything odd if you saw him rushing about. I told him you wouldn’t notice, but he does so like to play games.’

My Comments:

Now on his birthday, young Charley King has an actual drum used by the military. It’s a dream come true for the now twelve-year-old musician. The “Sweney boy” was no longer a boy, he was a neighbor and friend of the King family who would have a great influence on Charley’s future.

Charley Wants To Be A Drummer In The Civil War

“The family said Grace and they began to dish out dinner, starting with the youngest children.

“‘So you like the drum.’ Pennell said, as he distributed chunks of cornbread.

“‘I love it,’ Charley answered. ‘I led practically the whole school around town, and they all marched in line. well sort of a line…’

“‘Oh, we heard,’ Adeline said.

“‘People were talking about it?’ Charley asked.

“‘No, your mother means we actually heard it,’ Pennell clarified. ‘That is quite the loud drum. Necessarily so, of course, as it must be heard over the sounds of battle.’

“‘Hey yeah.’ Charley said, a thought forming in his mind. He looked over at his drum and thought about what a thrill it had been to lead his peers. And he was a good drummer – everyone said so.

“‘What if I was a Drummer Boy?’ he blurted out.

“‘I would say you already are.’ his mother replied.

“‘No, I mean, when the war starts. The army needs drummers don’t they, to help with a March and all sorts of things? But drummers don’t carry guns.‘

“Charley watched as his father drew a long breath, lying down his silverware beside his plate.

“‘Son, we already talked about this. You’re too young. Whether you’re carrying a gun or not, you would still be in danger.’

“‘But they wouldn’t fire on a drummer boy, would they?’

“‘The drummer marches in line with the rest of his company, Charley. Side-by-side. When one line fires on another, they are rarely discerning when it comes to their target. You are only 12 years old.’”

My Comments:

A fire is lit in Charley’s mind to become a drummer in the Civil War. Pennell and Adaline now have a challenge to discourage Charley from having such a dream.

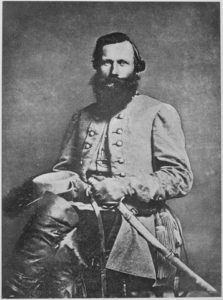

Captain Sweney Needs a Drummer For Company F of the 49th Pennsylvania

My Comments:

As Charley is marching about West Chester and playing his new drum, practicing as if he is a drummer in the Civil War. He encounters a man in a blue uniform with the insignia of a captain riding on a horse. Charley’s drumming had spooked the horse. The uniform caused Charley to not immediately recognize the man, but he looked familiar. But then Charley knew who the man on the horse was.

He is Benjamin Sweney, the next-door neighbor of the King family, now to be the captain of Company F of the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteers. At Charley’s father’s request, it was Sweney who had arranged for Charley to have a new drum as a birthday present. This chance meeting on a West Chester, Pennsylvania street would change Charley’s life.

“‘So, tell me, Charley, how long have you been drumming?’

“‘Forever, I guess,’ Charley shrugged. ‘I don’t really remember a time when I wasn’t playing in some way. I just like keeping time, I suppose.’

“‘Well you are skilled at it. I have a deep love of music and I greatly appreciate a kindred spirit..’

“Charley forced a smile.

“‘Thank you… sir, would you mind if I asked you a question?’

“‘Go ahead.’

“‘Well, if you’re a captain in the army, what are you doing in West Chester? Shouldn’t you be with your regiment?’

“‘Well,‘ Captain Sweney said. ‘I suppose I should, but at the moment I don’t have one. I’m here because Mr. Lincoln is looking for 300,000 men for three years of service. I’m to be captain of Company F in the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteers, but as of now, the 49th doesn’t exist. it will soon, though.’

My comments:

Captain Sweney and Charley begin to discuss about men volunteering to join the army. In particular Charley’s father and Charley himself.

“‘Oh, he sees it that way when it comes to his own duty, should his country need him,’ Charley explained, ‘just not when it comes to me. I love this country too, but I cannot go fight. I cannot even carry a drum.’

“Captain Sweney frowned.

“‘It sounds as if he wants to keep you safe. I don’t believe there is anything wrong with a father thinking that way.’

“‘Of course,’ Charley replied. ‘I understand that. I just… sorry, sir. I don’t mean to be rude.’

“‘Not at all. listen, your father wants you to be safe, and I understand that. My father wants me and my brother to be safe too, no matter how old we’ve gotten.’

“‘But I also understand your deep desire to come to the aid of your country. So… well, I can make no promises, Charley, but I will be head of a company… and a company needs a drummer. Perhaps I can speak with your father.’

“Charley tried to contain his excitement. He knew his father was serious about keeping him safe and he had no chance of changing his mind on his own. But maybe with the help of a captain in the army, Pennell might just see things differently.

“‘You would you do that for me?’ Charley said. ‘What if he doesn’t change his mind?’

“‘It cannot hurt to try,’ Captain Sweney replied. ’I’ll come by tomorrow morning and speak to him.’

“They did not have to wait long at all before Captain Sweney appeared on the block, making his way toward the King’s home. He was still in his uniform, riding his horse toward them. He stopped and tied the beast to the porch before walking to the door and knocking. Charley moved to answer it but his father gestured for him to sit back down and wait. A moment later, Captain Sweney was inside.

“‘I’ve not seen you for some time, Benjamin,’ his father said. ‘You’ve done quite well for yourself, I see.’

“‘As you as have you.’ Captain Sweney replied. ‘You have a fine home. It almost makes a man jealous to see such a fine picture of domestic life. A military tent is a little comfort.’

“‘Indeed, Pennell said. You, of course, know my son Charley. The other children are still upstairs, and my wife Adeline is in the kitchen. Would you like to come sit down and have breakfast?’

“‘That is very kind of you Pennell, I accept. Do you have any coffee?’

“‘I am certain we can brew some up for you,’ Pennell replied.

“‘So,’ his father said, ‘I understand you’ve spoken to my boy about being a drummer for your company.’

“‘Yes, Mr. King. I apologize if I overstep my boundaries. The boy nearly crashed into me while I was riding through town, and I happened to notice his considerable skill with the instrument.’

“‘I understand your company is to be part of the 49th Pennsylvania, organizing in September. Is that correct?’

“‘It is,’ Captain Sweney said. ‘Before you give me your thoughts on the matter of Charley’s joining, I do want to say that I am very understanding of your feelings on the matter. This is no small thing to be undertaken lightly. War is a dangerous proposition, for all involved. That said, precision is paramount when moving and positioning troops, and I have heard your son play. I venture to say he understands the importance of precision.’

“‘In music, certainly,” Pennell allowed, ‘but the streets of West Chester are not the fields of Virginia, Ben. And cannonballs do not discriminate between musket and drum.’

“‘That is true, but your boy will not be in the thick of it. When battle commences, he would be behind the company. I will make sure of that, he will stay safe.’

“‘How can you promise that?’ Charley heard his mother ask. ‘You have no control over what the other side will do. The Rebels will fire upon anyone in blue. They have no regard for age.’

“‘I will see to it myself,’ Captain Sweney replied. ‘As long as I stand – as long as I hold my command – I promise to ensure your son’s safety. He will not be hurt under my watch.’

“‘You’ll make it part of your duty to protect him?’ his father asked. ‘You give me your word?’

“‘On my honor,’ Captain Sweney said, ‘he will not come to harm.’

“Charley let out a long breath. They rose to their feet and walked out of the kitchen to where Charley was waiting. Behind them, he could see his mother standing with a hand over her mouth. The look on her face pained him deeply, but nothing could turn him back now.

“‘Well,’ the captain said, ” ‘I suppose you could hear all that from here. Enjoy the rest of your summer, Charley. come September, we muster.’”

My Comments:

Captain Sweney has made an unreasonable promise to Charley’s father and mother that he will keep Charley safe in battle. Perhaps Captain Sweney is naive. With this, twelve-year-old Charley King’s life takes a dramatic turn. He will be going off to fight in Mr. Lincoln’s Army as a drummer in Company F in the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteers. His drummer dream is to come true. Charley will train to become a soldier and he will participate in many Civil War battles. Charley will “See The Elephant,” and he will experience the horror of war firsthand.

The foundation of Lyon’s story about Charley King has been laid and from forward on the reader can enjoy Lyon’s blending of factual history and his storytelling fiction that weaves a believable story about Charley King, a mere twelve-year-old boy who became a drummer in the Civil War. Charley goes to war and “Sees the Elephant.”

Factual History of Company F of the 49th Pennsylvania

My comments:

From September 14, 1861 and on, the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Unit was very active in the Civil War. The unit would suffer casualties as it fought in many battles, 361 men would be lost. Company F fought battles in the Eastern Theatre and Charley King served as a drummer in many significant battles.

Casualties of the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Unit

- Nine officers were killed or mortally wounded.

- Significantly, Colonel Thomas M. Hulings died in action at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.

- 184 enlisted men were killed or mortally wounded.

- Disease always took a heavy toll in the Civil War. It killed 168 men of the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Unit.

- Charley King would become the youngest-documented soldier of either North or South to be killed in the Civil War. He suffered a mortal wound at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. He lingered until September 20, when he died at age thirteen.

Commanders of the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Unit:

- Colonel William H. Irwin, resigned on October 24, 1863.

- Lieutenant Colonel William Brisbane, was the commander at the Battle of Antietam.

- Lieutenant Colonel Baynton J. Hickman, was the commander at the Third Battle of Winchester.

- Colonel Thomas M. Hulings – Was killed at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.

Company F Members Featured in Charley:

- Benjamin Sweney – Captain.

- John Gray – Lieutenant.

- W. F. Wombacker – First Lieutenant.

- Charley E. King (Musician, drum.)

- Joseph “Joe” Keene – (Musician, fife.)

- Alfred Moulder – Private.

- Charles “Chuck” Butler – Private.

- Lenny Appleman – Private.

- Abel Tyson – Private.

- John Coon – Private.

- A notable member: Captain William Earnshaw, was the regiment’s chaplain, later the 8th Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic from 1879 – 1880.

Company F Order of Command:

- The People of the United States

- President Abraham Lincoln

- General Winfield Scott Hancock

- General George B. McClellan

- Major General William B. Franklin

- Brigadier General W. F. Smith

- Major Thomas Hulings

- Colonel William Irwin

- Captain Benjamin Sweney

- John Gray – Lieutenant

- First Lieutenant W. F. Wombacker

- Sergeant Philip Haines

- Don Jaun Wallings Sergeant/Lieutenant

Battles the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry and Charley King Fought In:

- Battle of Yorktown/Siege of Yorktown – Was part of the Peninsula Campaign and it was fought from April 5 to May 4, 1862.

- Battle of Williamsburg/Battle of Fort Magruder – Was part of the Peninsula Campaign and it was fought on May 5, 1862.

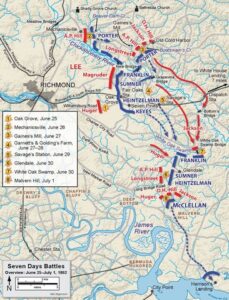

- Seven Days Battles -These were seven battles fought near Richmond, Virginia over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862. They were all part of the Peninsula Campaign.

- Battle of Garnett’s & Golding’s Farm – This battle was part of the Seven Days Battles. It was fought on June 27–28, 1862.

- Battle of Savage’s Station – This battle was part of the Seven Days Battles. It was fought on June 29, 1862.

- Battle of White Oak Swamp – Another battle of the Seven Days Battles. It was fought on June 30, 1862.

- Battle of Malvern Hill/Battle of Poindexter’s Farm – This battle was part of the Seven Days Battles. It was fought on June 29, 1862.

- Battle of South Mountain/Battle of Boonsboro Gap – This battle was part of Robert E. Lee’s and his Army of Northern Virginia Maryland Campaign. It was fought on September 14, 1862.

- Battle of Antietam/Battle of Sharpsburg – Was part of Robert E. Lee’s and his Army of Northern Virginia Maryland Campaign. It was the bloodiest one-day battle of the Civil War. The battle was fought on September 17, 1862, and is where Charley King was mortally wounded.

Battles the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry and Fought In After Charley King Died:

- Battle of Fredericksburg

- Battle of Chancellorsville

- Battle of Gettysburg

- Bristoe Campaign

- Second Battle of Rappahannock Station

- Mine Run Campaign

- Battle of Germania Ford

- Battle of the Wilderness

- Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

- Battle of North Anna

- Battle of Cold Harbor

- Siege of Petersburg

- Third Battle of Winchester

- Battle of Hatcher’s Run

- Appomattox Campaign

- Third Battle of Petersburg

- Battle of Sailor’s Creek

- Battle of Fort Stevens

My Recommendation of Charley:

Brendan J. Lyon’s novel Charley is a book that combines historical facts and creative fiction to tell a story as accurately as possible about Charley King. It’s a convincing effort. In Charley, Lyons blends factual history with believable and imaginative storytelling. Lyons is not unlike Michael and Jeff Shaara in this talent.

As I read Charley, I began to think that Lyons had discovered a diary of Charley’s, a diary where Charley kept a detailed record of his short life and times. He gets the history right and fills in the unknown story about Charley King with his own imagination. The result is an intriguing, entertaining, and informative book.

I found Charley to be a page-turner and I’m sure you will too. I wholeheartedly recommend Brendan J. Lyons’ book, Charley – The True Story of the Youngest Soldier to Die in the American Civil War to you.

Charley will help you to Learn Civil War History.

Book Information From Amazon:

Product details

Publisher : Brookline Books (July 15, 2023)

Language : English

Paperback : 160 pages

ISBN-10 : 1955041067

ISBN-13 : 978-1955041065

Reading age : 12 – 18 years

Grade level : 7 – 9

Item Weight : 3.2 ounces

Dimensions : 5.8 x 0.6 x 8.9 inches

Best Sellers Rank: #763,430 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

#19 in Teen & Young Adult United States Civil War Period History

#151 in Teen & Young Adult Historical Biographies

#4,477 in Military Leader Biographies

Customer Reviews: 5.0 5.0 out of 5 stars 7 ratings