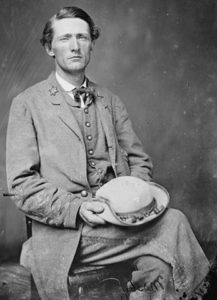

John Singleton Mosby – The Gray Ghost Of The Confederacy

Virginian and Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby was from just south of Charlottesville. He led his famous partisan ranger unit called Mosby’s Rangers, but it was officially the 43rd Battalion of the Virginia Cavalry. Mosby took his cavalry on raids known for their quickness. After a raid, Mosby and his men would escape from pursuing Yankees by blending in with the local people in their towns and farms. They hid in plain sight. Mosby was so effective with his raids that an area of Virginia he dominated became known as Mosby’s Confederacy. Because of his ability to disappear after a raid, Mosby was called the “Gray Ghost.”

A Kick In The Face

Mosby had a reputation for being cantankerous and ornery. He was a tough fighter and scrapper. Mosby wouldn’t give an inch. A story circulating after the Civil War told about how a horse kicked Mosby hard in the face while he was visiting Charlottesville. He was seriously injured by the horse hoof’s blow to his head. Mosby was knocked out cold and it was feared he might be dead. Mosby was rushed over to the University of Virginia’s infirmary for treatment. A young intern there leaned over the now semi-conscious former Confederate raider, the “Gray Ghost,” and asked him, “What’s your name?” The prickly Mosby was now in a semi-conscious state. He remained true to his character and replied to the young intern, “None of your damn business.” A nearby surgeon who was preparing to possibly operate on the Gray Ghost heard what Mosby said. The surgeon was familiar with Mosby’s reputation and he exclaimed, “He’s conscious all right.”

Young Mosby Goes To Jail – Becomes A Lawyer

When he was a young lad, it seemed unlikely that John Singleton Mosby would ever become a soldier. He was often sick, picked on, and bullied by other boys at school. But John had an inner strength and he learned to fight back against challengers. While studying Classical Studies at the University of Virginia, he got into a fight with a fellow student. Mosby drew a pistol and shot his adversary in the neck. He was arrested, sent to jail for a year, fined $500, and kicked out of the university. In jail, Mosby’s health declined and because of his bad health, he received a pardon from Virginia’s governor. Oddly, Mosby became friends with the prosecuting attorney who helped send him to jail. In jail, and after being released, this attorney gave Mosby use of his law library. Mosby earnestly studied the attorney’s law books and in 1854 he was admitted to the bar.

Mosby’s Family Life – A Combination of Joy and Loss

John Singleton Mosby married Pauline Clarke and began a law practice in Howardsville, Virginia in 1857. John and Pauline began their family. Daughters May and Beverly were born before the Civil War and John Singleton Mosby Jr., was born in 1863 while the Civil War was raging. Son Lincoln was born in 1865 and Victoria was born in 1866. Isn’t it curious that the Gray Ghost of the Confederacy would name his son Lincoln? Daughter Pauline was born in 1869 and Ada came in 1871. Two Mosby sons perished at very young ages. Son George was born in 1873 and he died in 1874. Son Alfred was born and died in 1876 as did his wife Pauline.

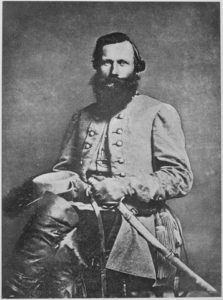

The Civil War Comes, Mosby Joins the Confederate Army, Is Captured

Before the Civil War, the man who became known as the “Gray Ghost” of the Confederacy at first opposed secession. However, he joined the Confederate army and was a member of the “Confederate Volunteers.” In this company, he fought as a private at the Battle of First Manassas/Bull Run. Mosby demonstrated great skill and capability at gaining intelligence about Yankee operations. In light of this, J. E. B. Stuart made Mosby a First Lieutenant in early 1862. Mosby became a part of Stuart’s cavalry scouts. Mosby was captured in 1862, He spent ten days in the Old Capital Prison in Washington, D.C. before being paroled in a prisoner exchange. He paid attention while in prison. During a temporary time at Fort Monroe, he observed an increase of ships in Hampton Roads. Ships were arriving with thousands of Union soldiers. These men were on their way to reinforce John Pope in his Northern Virginia Campaign. After his ten days in prison, Mosby went to Richmond and conveyed this crucial information to General Robert E. Lee.

Mosby’s Rangers

The Confederate Congress passed the Partisan Ranger Act in April 1862. This act, “provides that such partisan rangers, after being regularly received into service, shall be entitled to the same pay, rations, and quarters, during their term of service, and be subject to the same regulations, as other soldiers.”

J. E. B. Stuart was Mosby’s commanding officer and after the December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, they together made raids into Union lines. These raids went into Prince William, Fairfax, and Loudoun counties in Virginia. Their goal was to mess up and muddle Union communication, material, and replenishments between Fredericksburg and Washington, D. C., while also providing for themselves. It was later that year when Mosby and his raiders joined up in Loudoun County with a mishmash of other cavalrymen.

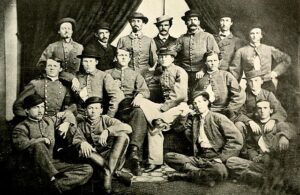

By January 1863, Mosby was a Major and he had command of the 43rd Virginia Cavalry, a partisan unit that became known as “Mosby’s Rangers.” The 43rd Virginia Cavalry was a unit of the Army of Northern Virginia and followed the commands of Robert E. Lee and J. E. B. Stuart. There were approximately 1,900 men who served from January 1863 to April 1865 in the 43rd Virginia Cavalry. Special rules were given to this cavalry unit of partisan rangers. They were allowed to share the spoils of war they gathered on their raids and they had no camp duties to worry about.

Mosby’s Rangers made quick raids on Union supply lines and bedeviled Union couriers. He was very successful and the 43rd Virginia Cavalry was highly regarded for their effectiveness. It seemed that Mosby’s Rangers were able to disappear and escape without a trace after a raid as if they were ghosts. They would spread themselves into the local civilian populations, mixing in, dispersing, and disappearing as if normal civilians and not combatants. This is how Mosby gained the nickname “Gray Ghost.”

Fairfax Court House Raid and General Stoughton Capture

Mosby is perhaps best remembered for his inside Union lines on March 9, 1863, gutsy raid on Fairfax Court House, Virginia. Mosby and his Rangers made a nighttime raid on the small town. Union Brigadier General Edwin H. Stoughton was captured along with three more officers and other Yankee soldiers. Mosby claimed a deserter of the 5th New York Cavalry who had joined up with his Rangers, provided information that aided in the raid.

Mosby wrote in his memoirs that he came upon General Stoughton while he was asleep in bed, apparently after an evening of revelry and drinking. Mosby slapped Stoughton on his backside, “on his bare back,” to wake him. Stoughton then asked what was this all about. The Gray Ghost then asked Stoughton, “Do you know Mosby, general?” Stoughton answered, “Yes! Have you got the rascal?” Mosby responded, “I am Mosby.” Then he told Stoughton, “Stuart’s cavalry has possession of the Court House; be quick and dress.”

Mosby’s raid on Fairfax Court House was very successful. He and his twenty-nine men had captured General Stoughton, two captains, thirty enlisted men, and fifty-eight horses. Not even a single shot was fired during the raid. When President Abraham Lincoln learned of the Gray Ghost’s raid he said, “I can make more generals, but horses cost money.”

Mosby’s Rangers Raids in May and June of 1863

- On May 3, Mosby’s Rangers successfully surprised a Union Cavalry Regiment near Warrenton Junction, Virginia. This is known as the Warrenton Junction Raid. The Union 1st (West) Virginia Cavalry was protecting a supply depot. The Union casualties killed or wounded were six officers and fourteen men, plus supplies. Mosby’s casualties were one killed and no fewer than thirty either wounded or captured. Note: West Virginia soon became a state on June 20, 1863.

- On June 10, Mosby’s Rangers crossed the Potomac River and made a raid on Seneca, Maryland where Yankee cavalry was camped. They were successful at defeating the Sixth Michigan Cavalry and burned their camp. J. E. B. Stuart was pleased with Mosby’s Seneca raid.

- Next, J. E. B. Stuart again had Mosby’s Rangers cross the Potomac River at Rowser’s Ford. Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia were on their way north into Union land. It was June 27 and the Battle of Gettysburg was ominously looming, soon to occur on July 1 – 3. At night on June 27, with Mosby already crossing the Potomac at Rowser’s Ford, J. E. B. Stuart’s Cavalry also crossed the Ford. J. E. B. Stuart and his cavalry were now separated from Robert E. Lee and unable to give him scouting information. J. E. B. Stuart would not arrive at the Battle of Gettysburg until the afternoon of July 2. Stuart received a harsh rebuke from Lee regarding his late arrival. Lee said to him, “Well, General Stuart, you are here at last.” For Lee, those were harsh words of admonishment to Stuart.

Some Civil War historians say that a possible reason for Lee having a delay of important cavalry information at Gettysburg was because of Mosby’s success at Rowser’s Ford. Following that, J. E. B. Stuart also crossed at Rowser’s Ford. Thus putting his cavalry, the eyes and ears of important intelligence gathering, out of communication with Lee as he marched the Army of Northern Virginia northward, ultimately to Gettysburg. This continues to be popular a topic of Civil War debate and speculation.

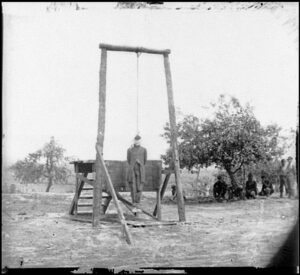

Executions

The Gray Ghost and his Rangers did not go unnoticed by General Ulysses S. Grant. Grant wanted the disruption, and loss of men, horses, and materials to end. Mosby was a definite drag on the Union’s war effort. Grant told Major General Philip Sheridan to proceed with this drastic action:

“The families of most of Mosby’s men are know[n] and can be collected. I think they should be taken and kept at Fort McHenry or some secure place as hostages for good conduct of Mosby and his men. When any of them are caught with nothing to designate what they are hang them without trial.”

This resulted in the execution of six of Mosby’s rangers on September 22, 1864, when they were captured out of uniform, that is as spies, at Front Royal, Virginia. One of those executed, William Thomas Overby, was offered to have his life spared if only he would tell of Mosby’s location. Overby refused the offer. His last words were, “My last moments are sweetened by the reflection that for every man you murder this day Mosby will take a tenfold vengeance.” After the executions, one Yankee spitefully pinned a note to one of the bodies. The note read, “This shall be the fate of all Mosby’s men.”

Mosby responded in a like way to the execution of his cavalrymen. The Gray Ghost notified General Robert E. Lee and James Seddon, the Confederate Secretary of War, that he would execute Union prisoners.

Seven Yankee prisoners were chosen in a “death lottery” to be executed at Rectortown, Virginia on November 6, 1864. One of those chosen for execution was only a young drummer boy. With a showing of mercy, his life was spared. In a second “death lottery” another man was selected to take the drummer boy’s place on the gallows.

By circumstance, not all of the seven Yankees selected for death were executed. Three of them were hanged, two of them managed to escape, and two were left for dead after being shot in the head. Incredibly, the two shot in the head survived.

Executions End

Apparently, the Gray Ghost had had enough of the brutal and mutual prisoner executions. Mosby wrote to Philip Sheridan, the commander of the Shenandoah Valley Union troops, on November 11, 1864. Mosby asked Sheridan if they both could refrain from executing more men. Mosby wrote that they ought to begin acting with humanity toward prisoners of war. Sheridan agreed with Mosby and the executions ended.

Mosby Was Wounded Three Times

- The Gray Ghost was first wounded on August 12, 1863, at Annandale, Virginia. He was struck by a bullet in his thigh and side. He recovered quickly and returned to his command a month later.

- Mosby’s second wounding was on September 14, 1864. This wound was more serious than the first one. He was challenging and taunting a Union regiment by riding back and forth in front of it, boldly tempting fate and death. A Yankee bullet hit Mosby’s revolver’s handle before entering his groin. Mosby was able to escape, but only barely kept on his horse. He was on crutches during a three-week recovery and then returned to his command. Fate was kind to the Gray Ghost.

- Mosby’s third wound occurred on December 21, 1864. He was having food with a family near Rector’s Crossroads, Virginia when a Yankee ball came through a window and struck him two inches below his bellybutton. Mosby staggered into a bedroom. Quickly and clearly thinking he hid his jacket, which had his identifying rank insignia on it. A Union officer came into the home and inspected Mosby’s wound. He did not know the wounded man was John Singleton Mosby, the Gray Ghost. The officer determined the abdomen wound to be mortal. Mosby was left for dead. It took him two months to recover, and then once again he returned to the field.

Mosby’s Surrender

General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. The Civil War was effectively over although some dwindling skirmishes followed. The Gray Ghost and his Rangers standing after Lee’s surrender was tenuous. “Marauding bands” were not given parole by the surrender terms. These marauding bands, which Mosby’s Rangers were, were to be destroyed.

On April 12, Mosby received a letter from General C. H. Morgan, who was a member of General Winfield S. Hancock’s staff. This letter notified Mosby that if he and his Rangers were to surrender, then they would have the same surrender terms as Lee received at Appomattox Court House. The Gray Ghost disbanded his cavalry unit on April 21 and soon many of his former Rangers went to Winchester, Virginia to surrender. There they received their paroles and the Civil War was over for them. They went home, but some of Mosby’s Rangers remained with him. Their war was not yet over.

Mosby himself was not anxious to surrender and refused to do so, he and his remaining Rangers continued on and made a raid near Lynchburg, Virginia in May. Mosby knew there was a $5,000 bounty on his head. Mosby was now a colonel but was in hiding at Lynchburg because of the high bounty. He disbanded his remaining men and they left on their way home. Mosby was still in hiding when General Ulysses S. Grant intervened and the Gray Ghost was given parole. Colonel John Singleton Mosby surrendered on June 17, 1865, he was one of the last officers of the Confederacy to surrender.

Mosby was born on December 6, 1833, and he died on May 30, 1916.

Gray Ghost Quotes

“The military value of a partisan’s work is not measured by the amount of property destroyed, or the number of men killed or captured, but by the number he keeps watching.”

– John S. Mosby.

“War loses a great deal of its romance after a soldier has seen his first battle. I have a more vivid recollection of the first that the last one I was in. It is a classical maxim that it is sweet and becoming to die for one’s country; but whoever has seen the horrors of a battlefield feels that it is far sweeter to live for it.”

– John S. Mosby.

“Only three men in the Confederate army knew what I was doing or intended to do; they were Lee and Stuart and myself.”

– John S. Mosby.