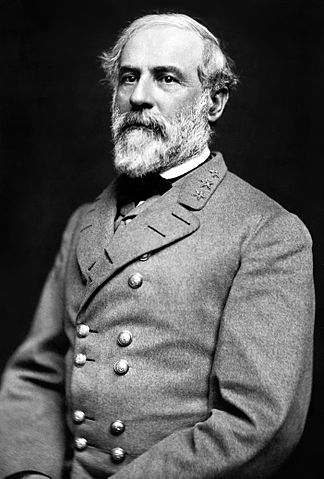

Robert E. Lee’s Masterpiece

May 1, 1863

At the Battle of Chancellorsville Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia is outnumbered by Union Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker’s Army of the Potomac by more than two to one, yet Robert E. Lee and his “right-arm” General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, defeat the Federals. Chancellorsville is “Lee’s Masterpiece.”

Lee’s victory at Chancellorsville will provide him his path to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and another meeting with the Army of the Potomac in early July of 1863.

Despite being Lee’s most canny and skillful victory, Chancellorsville will also bring a great loss to General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia.

Note: Chancellorsville is a brick plantation house located in the area known as the Wilderness, it is not an actual town.

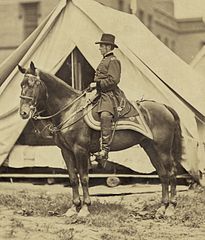

Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker

General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker was a bombastic, egotistical, and conceited individual. Hooker was a person who thought his ends always justified his means, he would often disobey orders, jump over levels of command, or just flat out lie in order get what he wanted. Joe Hooker was a handsome six-footer and popular with the women. However, among the men Hooker served with he was not popular. He was not well liked or trusted.

General Joseph Hooker’s nickname of “Fighting Joe” came about by accident. The New York newspaper Courier and Enquirer had received a report about some action Hooker was involved in during McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign. The heading of the report said: “Fighting – Joe Hooker” and it was meant to indicate that the report should be used to add more information to an already existing article about Joe Hooker’s part in the battle.

Due to an error at the newspaper, this new report was treated as a separate article and was given the heading of: “FIGHTING JOE HOOKER” with the hyphen omitted. The newspaper readers loved the nickname and it stuck. At first, Hooker himself did not much care for the nickname, but as time progressed, he liked it more and more.

With reservations, President Lincoln gave Joe Hooker command of the Army of the Potomac on January 25. Hooker was replacing General Ambrose Burnside, who’d been a weak leader. Burnside had failed at Fredericksburg and later brought about a blunder known as the “Mud March.” Burnside’s time as commander of the Army of the Potomac ended.

On To Richmond!

The rallying goal for the North was: On to Richmond! If the Army of the Potomac could take the Confederate capital of Richmond, then the Confederate cause would be broken and the war won. Burnside’s loss at Fredericksburg left General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia firmly dug-in with a defensive position at Fredericksburg, and blocking the Army of the Potomac’s path to Richmond. Now with Fighting Joe Hooker as the new commanding general, the Army of the Potomac would launch a fresh offensive on Richmond.

Joe Hooker went to work preparing the Army of the Potomac for his plans. Hooker reorganized the army and made changes in commands. The Army of the Potomac at this time consisted of nearly 150,000 troops and was the largest mobilized field army in the world.The Army of the Potomac had become dispirited after the Union loss at Fredericksburg the previous December, but with Joe Hooker it regained its morale. Joe Hooker is a fighter! President Lincoln gave General Joe Hooker the freedom to make his own plans for the offensive campaign that would take place with the arrival of spring and the drying of the muddy winter roads. Lincoln did require two things of Hooker; that he go on the offensive as soon as possible, and that he leave Washington guarded.

May God Have Mercy On General Lee

Hooker planned to have one wing of his army march 40 miles upstream of the Rappahannock River and then cross it and the Rapidan River at fords located west of Confederate defenses. These troops then would move east and attack the Confederate left flank. The rest of the Army of the Potomac would cross the Rappahannock at a point below Fredericksburg to harass the Confederates there.

“Fighting Joe” Hooker thought his plans were good, his plans in fact, were not bad at all, and he was confident. Before the campaign Hooker said:

“My plans are perfect and when I start to carry them out, may God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.”

Lee Is Greatly Outnumbered

Hooker began his troop movements on April 27. General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia had spent the winter entrenched at Fredericksburg. Lee’s troops numbered about 61,000 men and Hookers’ troops about 134,000 men, Lee had less than half the men of Hooker. By April 30, Hooker had 50,000 men at a brick mansion named Chancellorsville. Chancellorsville was located at a crossroads in the dense, thicket-like, scrubby, secondary growth known as the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, ten miles west of Fredericksburg.

General Lee and his “right hand” General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson had correctly sized up the situation. They realized the Yankees at Chancellorsville, and not those who were opposite them and below Fredericksburg, were the main threat of Hooker’s offensive advance. The Confederates left a division to hold the Fredericksburg entrenchments, and the greater part of Lee’s army headed west toward Chancellorsville.

Hooker Wants To Embolden The Enemy To Attack

On the morning of May 1, Jackson’s troops met up with Hooker’s men a few miles east of Chancellorsville. Despite having a superior number of troops, Hooker fell back to a defensive position in the Wilderness terrain around Chancellorsville. The Union troops put up entrenchments around General Hooker’s Chancellorsville headquarters.

Major General Darius N. Couch was the Army of the Potomac’s senior corps commander and he told General Hooker there was disappointment among the army leaders that Hooker had chosen a defensive posture at Chancellorsville. Couch himself, had favored an offensive strategy. “Fighting Joe” Hooker told General Couch:

“It is all right, Couch, I have got Lee just where I want him; he must fight me on my own ground.”

Couch was in disbelief with what Hooker said to him:

“To hear from his own lip that the advantages gained by the successful marches of his lieutenants were to culminate in fighting a defensive battle in that nest of thickets was too much, and I retired from his presence with the belief that my commanding general was a whipped man.”

Hooker distributed to his corps commanders a circular including these words:

“The major general commanding trusts that a suspension in the attack to-day will embolden the enemy to attack him.”

Lee And Jackson Meet At Night

Lee and Jackson would meet the night of May 1 to decide on a plan, supposedly while sitting on cracker barrels or boxes. What these two great Confederate generals conceived during their night meeting was one of the most remarkable military gambles ever devised.On the coming day of May 2, “Fighting Joe” Hooker was going to have emboldened enemy attacking him.

NEXT: Chancellorsville May 2, 1863

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!