Virginia seceded from the Union on April 17, 1861 to become part of the Confederate States of America. While the people of Virginia east of the Allegheny Mountains were pleased with the state’s secession, the Virginians who lived west of the Alleghenies, were not pleased to secede from the Union.

Mountaineers and Tidewater Aristocrats

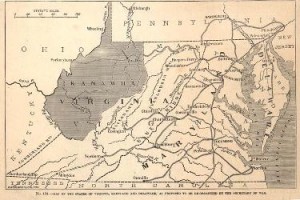

These two parts of Virginia that were separated physically by the Alleghenies, were also separated from one another in other ways. Western Virginia was made up of thirty-five counties located west of the Shenandoah Valley and north of the Kanawa River. In 1860, this part of Virginia had one quarter of Virginia’s white population. This area of Virginia’s geography is very rough country made up mostly of hills and steep mountainsides with narrow valleys. The geography of western Virginia separated it significantly from the more lowland eastern tidewater part of the state. It’s fair to say that Western Virginia was a land of mountaineers.

The western part of Virginia was more closely tied by roads and rivers to its northern neighboring states of Ohio and Pennsylvania than it was to eastern Virginia. The two sections of Virginia were different in geography, culture, and economics as the western part identified more with Ohio and Pennsylvania in these regards. The western Virginia city of Wheeling was the largest city in that area and it is a mere 60 miles from Pittsburgh. In contrast, from Wheeling to Richmond it was 330 miles! An important difference between western and eastern Virginia was that it was rare to find slave owners and slaves in the rugged country of the mountaineers.

The mountaineers looked at the people of eastern Virginia as “tidewater aristocrats” and because of the larger population in the eastern part of the state, the mountaineers were underrepresented in the state legislature. The tidewater aristocrats dominated Virginia’s state government. The Virginia state legislature had passed laws and taxes that favored the eastern tidewater aristocrats more so than they did the mountaineers of western Virginia. The mountaineers needed more roads and railroads, and other internal improvements, that instead often found their way to the tidewater aristocrat’s eastern part of the state.

Discord had been stewing for years amongst the two sections of Virginia before Virginia seceded from the Union. Separate statehood for western Virginia was not a new idea at the start of the Civil War, and now it would come to the vanguard. With Virginia’s secession from the Union, the unhappiness and disagreement between the mountaineers and the tidewater aristocrats of Virginia only increased. Only five of the thirty-one delegates from northwestern Virginia voted for the Virginia secession ordinance on April 17, 1861. The mountaineer people of Virginia rejected the secession ordinance ratification by a margin of three to one. The Virginian mountaineers had little interest in secession from the Union, but it came because of the domination of votes and representation of the pro-secession eastern part of Virginia.

Wheeling Convention

On June 11, 1861 mountaineer Unionists met at a convention in Wheeling. The focus of this convention was separate statehood for western Virginia. However, there was a hurdle that stood in the way of western Virginia’s statehood, it was something called the United States Constitution.

Seems that Article IV, Section 3, of the United States Constitution requires consent of the legislature to form a new state from the territory of an existing one. Now, as hard as it might be to believe, the Confederate legislature over in Richmond wasn’t eager to allow western Virginia to become a separate state … and one that would be in the Union to boot. For the mountaineers and their quest for their own state, there just had to be a solution to this United States Constitution problem, someway, somehow.

The answer for western Virginia was for the Wheeling convention to ingeniously form its own Virginia “restored government.” You see, that Confederate legislature over east in Richmond, that secessionist one, is illegal and so the Wheeling mountaineers declared all state offices vacant. The Wheeling convention appointed new state officials on June 20. Francis Pierpoint was now governor of Virginia, and the new state capital was now in Wheeling. All these changes, as far as the Unionist western Virginia mountaineers were concerned, restored the state of Virginia.

Although this new Virginia legislature was in place, it really represented only one-fifth of Virginia, that being the mountaineers of the northwest counties. Nonetheless, it elected two United States senators from Virginia, and on July 13, 1861 these senators were seated by the United States Senate. Soon too, the United States House of Representatives had three congressmen from western Virginia.

In effect, there now was a Union Virginia claiming to represent all of Virginia, but actually only being made up of the mountaineer northwest part of the state, and there was a Confederate Virginia with its government in Richmond with its patronage of “tidewater aristocrats” who had seceded from the Union. President Abraham Lincoln recognized the Pierpoint administration as the government of Virginia. Obviously, President Lincoln was not going to recognize Virginia’s Confederate version of government as legitimate.

The Wheeling convention ended, and then it reconvened in August, 1861. Now a long debate began between separatists and a conservative minded faction who thought it improper that the new legislature was claiming to represent the entire state. In reality, the new legislature only represented the mountaineers of western Virginia, and this region only consisted of one-fifth of all of Virginia’s counties. Nevertheless, despite this debate, the Wheeling convention continued to move forward with its agenda … to form a new state.

Kanawha and an Ordinance of Dismemberment

On August 20, the Wheeling convention adopted what was called an “ordinance of dismemberment.” An ordinance for separate statehood had now been created. This ordinance would be subject to ratification on October 24, 1861 by the voters. Voters would also be able at this time to elect delegates for a constitutional convention, the purpose of which was for the formation of a new state to be named “Kanawha.” [The name “Kanawha” is an Native American word. It is believed to mean “place of white stone.” ]

Now, there were some military concerns that had to be handled concurrently with all this new state conventioning and formation going on in western Virginia. I will discuss the military operations of western Virginia completely in a future post, where they can be addressed fully and receive the attention they deserve. Important military assets such as the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the Ohio River were integral to western Virginia and their control was desired by both Yankees and Rebels. Suffice it to say for now, that Union military efforts in western Virginia were sufficient enough to rid the area of Confederate military problems, thus clearing the way for a new state to come about. This brief mention of the military operations in western Virginia is not to short-change them, they were significant. Indeed, without Union military dominance over Rebel troops in western Virginia, the formation of a new state would not have been possible.

Union military success in western Virginia allowed the October 24, 1861 referendum to occur. Voter turn-out was small, and voters (those of a Rebel ilk) in more than a dozen counties actually boycotted the election. The end result however, was that the creation of a new state was strongly endorsed.

Boundaries Set

Boundaries for the new state were set during the constitutional convention held in January, 1862. There would be fifty counties in the new state and the new state would not be called Kanawha, but instead West Virginia. On May 23, 1862 West Virginia was sanctioned by the restored legislature of Virginia.

The United States Congress would not allow a slave state to enter the Union, so first a bill requiring emancipation in West Virginia was passed in the United States Senate in July, 1862. It passed in the United States House of Representatives the following December. West Virginia accepted emancipation as a condition to statehood.

The eastern aristocrats still had their Confederate state of Virginia, but they lost some state territory as on July 4, 1863, the new state of West Virginia joined the Union.

West Virginia became the 35th state of the Union.

Declaration of the People of Virginia

Represented in Convention at Wheeling

June 13, 1861

The true purpose of all government is to promote the welfare and provide for the protection and security of the governed, and when any form or organization of government proves inadequate for, or subversive of this purpose, it is the right, it is the duty of the latter to alter or abolish it. The Bill of Rights of Virginia, framed in 1776, reaffirmed in 1860, and again in 1851, expressly reserves this right to the majority of her people, and the existing constitution does not confer upon the General Assembly the power to call a Convention to alter its provisions, or to change the relations of the Commonwealth, without the previously expressed consent of such majority. The act of the General Assembly, calling the Convention which assembled at Richmond in February last, was therefore a usurpation; and the Convention thus called has not only abused the powers nominally entrusted to it, but, with the connivance and active aid of the executive, has usurped and exercised other powers, to the manifest injury of the people, which, if permitted, will inevitably subject them to a military despotism.

The Convention, by its pretended ordinances, has required the people of Virginia to separate from and wage war against the government of the United States, and against the citizens of neighboring State, with whom they have heretofore maintained friendly, social and business relations:

It has attempted to subvert the Union founded by Washington and his co-patriots in the purer days of the republic, which has conferred unexampled prosperity upon every class of citizens, and upon every section of the country:

It has attempted to transfer the allegiance of the people to an illegal confederacy of rebellious States, and required their submission to its pretended edicts and decrees:

It has attempted to place the whole military force and military operations of the Commonwealth under the control and direction of such confederacy, for offensive as well as defensive purposes.

It has, in conjunction with the State executive, instituted wherever their usurped power extends, a reign of terror intended to suppress the free expression of the will of the people, making elections a mockery and a fraud:

The same combination, even before the passage of the pretended ordinance of secession, instituted war by the seizure and appropriation of the property of the Federal Government, and by organizing and mobilizing armies, with the avowed purpose of capturing or destroying the Capitol of the Union:

They have attempted to bring the allegiance of the people of the United States into direct conflict with their subordinate allegiance to the State, thereby making obedience to their pretended Ordinance, treason against the former.

We, therefore the delegates here assembled in Convention to devise such measures and take such action as the safety and welfare of the loyal citizens of Virginia may demand, having mutually considered the premises, and viewing with great concern, the deplorable condition to which this once happy Commonwealth must be reduced, unless some regular adequate remedy is speedily adopted, and appealing to the Supreme Ruler of the Universe for the rectitude of our intentions, do hereby, in the name and on the behalf of the good people of Virginia, solemnly declare, that the preservation of their dearest rights and liberties and their security in person and property, imperatively demand the reorganization of the government of the Commonwealth, and that all acts of said Convention and Executive, tending to separate this Commonwealth from the United States, or to levy and carry on war against them, are without authority and void; and the offices of all who adhere to the said Convention and Executive, whether legislative, executive or judicial, are vacated.