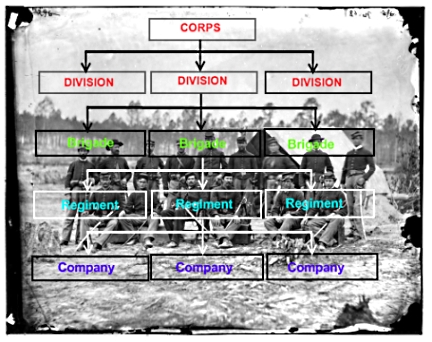

Here is an explanation of the basic way both the Union and Confederate armies were organized. The units are listed from the largest to the smallest. The descriptions below can be considered the ideal or desired make up of the units. As the Civil War progressed, the size of the various units would change due to loss of men by disease, death, or injury. The force of men an army could bring would be added to, and subtracted from, with the ebb and flow of war.

Army – An army is the largest field force unit of military organization. The Union armies were commanded by a major general and were usually named after rivers (for example, the Army of the Potomac). The Confederate armies were commanded by a general and were usually named after the area from which they were based (for example, the Army of Northern Virginia). The way of naming the armies was not always followed by either the North or the South and exceptions can be found, sometimes or often leading to confusion.

A confusing example of the way armies were named is this example: the Union had the Army of the Tennessee, while the Confederates had the Army of Tennessee. An army was further divided into Corps.

Corps – A corps was commanded by a brigadier general or a major general for the Union, and with the Confederate States of America a corps was commanded by a lieutenant general. Major General George B. McClellan and President Abraham Lincoln organized the first corps in the Union Army in March, 1862. In 1862, the Confederates began organizing their armies using corps in September in the east, and in November in the west.

Prior to arranging corps, the Confederates had sometimes (and informally) used what were called “wings” or “grand divisions” to further group their armies. A corps would be made up of two or more divisions and each corps used a Roman numeral for its designation. The corps were also often referred to using their commander’s name.

Division – A division was the second largest unit making up an army. For the Union, a division was commanded by a brigadier general or a major general. For the Confederacy, a division was commanded by a brigadier general, and sometimes, but it was rare, by a major general. A division would be divided into usually 2 to 6 brigades. The Confederate divisions tended to be larger in manpower than the Union divisions and would be made up of more brigades. Some divisions in Confederate armies were of equal size to one corps from a Union army.

Brigade – A brigade was commanded by a brigadier general or maybe a senior colonel. A brigade was divided into regiments, usually two to six regiments to a brigade. The Confederate brigades were more apt to be made up regiments from the same state, than brigades in the Union armies.

Regiment – A regiment was commanded by a colonel. The regiment was probably the army organization unit that a soldier felt like he most belonged to. A regiment was made up of men from the same area of a state, mainly because they were raised by the various state governments. At least during the early part of the Civil War, a regiment would have men who were friends or neighbors back home, or were relatives. These regiments chose their own officers by electing them. Typically, a regiment was made up of 10 companies, with each company having 100 men. So, if mustering men for service went well, there were 1000 men in each regiment. A battalion was the name used for a regiment that had not mustered a full 10 companies with 100 men in each company.

Company – A company was commanded by a captain. With perfect army organization and strength, a company had 100 men. But because of disease and other causes (such as soldiers being killed in battle!), by 1862 a company might only have 30 to 50 soldiers. Companies were officially designated by letters or numbers, but often a company had an unofficial designation, often a nickname.

Does reading about Civil War history from long and dry academic-like books bog you down and cause you to lose interest? Would you like to read interesting stories based on facts of the Civil War, stories that inform you and move along with the war’s history? Does having to read from cover to cover tire you and cause you to drag through a history book? Would you prefer the freedom to skip around in a book and learn story-by-story about the Civil War? If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, then the factual stories in 125 Civil War Stories and Facts will help you learn Civil War history. The stories are informative and entertaining and it’s a fun way to learn about the Civil War. Do books like Civil War Trivia and Fact Book by Webb Garrison or The Civil War: Strange & Fascinating Facts by Burke Davis interest you? Then you will find 125 Civil War Stories and Facts follows in their tradition of providing the reader with rich and interesting information about the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 125 Civil War Stories and Facts now!

Does reading about Civil War history from long and dry academic-like books bog you down and cause you to lose interest? Would you like to read interesting stories based on facts of the Civil War, stories that inform you and move along with the war’s history? Does having to read from cover to cover tire you and cause you to drag through a history book? Would you prefer the freedom to skip around in a book and learn story-by-story about the Civil War? If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, then the factual stories in 125 Civil War Stories and Facts will help you learn Civil War history. The stories are informative and entertaining and it’s a fun way to learn about the Civil War. Do books like Civil War Trivia and Fact Book by Webb Garrison or The Civil War: Strange & Fascinating Facts by Burke Davis interest you? Then you will find 125 Civil War Stories and Facts follows in their tradition of providing the reader with rich and interesting information about the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 125 Civil War Stories and Facts now!

Civil War Army Organization

Shown below is a chart to help clarify Civil War army organization somewhat. The soldiers shown in the background are members of the Petersburg, Virginia Detachment of the 3d Indiana Cavalry.

Order of Rank

Listed from top to bottom are the highest ranks of officers and gentlemen, all the way down to the lowly, but backbone of the army, private.

- General

- Lieutenant General

- Major General

- Brigadier General

- Colonel

- Lieutenant Colonel

- Major

- Captain

- First Lieutenant

- Second Lieutenant

- Sergeant

- Corporal

- Private

Civil War Army Organization

By Civil War Trust Historian Garry Adelman

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!