Seeing the Elephant – How it Feels to be Under Fire

During the Civil War, soldiers would speak about “Seeing the elephant.” The “elephant” was battle, combat, being under enemy fire.

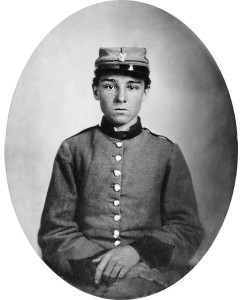

Both the Confederacy and the Union had armies made up mostly of volunteers, with much fewer soldiers actually belonging to the Regular Army. Whether volunteer or Regular Army, the vast majority of these young men had never faced enemy fire. Many were away from home for the first time in their young lives. They had lived quietly and peacefully in small towns, farms, or cities. Now, they were learning to kill, and facing the great possibility of being killed. As these men trained and marched, preparing for battle, the thought of “Seeing the elephant” for the first time weighed on their minds.”It’s just like shooting squirrels, only these squirrels have guns.”

— A Federal veteran instructing new recruits in a musket drill.

“Bang, bang, bang, a rattle, de bang, bang, bang, a boom, de bang…whirr-siz-siz-siz–a ripping, roaring, boom, bang!”

— Confederate Sam R. Watkins describing a “fire fight.” Sam Watkins was twenty-one years old and from Columbia, Tennessee when he joined up to fight in the Civil War. He kept a journal and recorded his experiences and thoughts during the war. His words give us great insight into the Civil War.

“It was eyes right, guide center! Close-up, guide right, halt, forward, right oblique, left oblique, halt, forward, guide center, eyes right, dress up promptly in the rear, steady, double quick, charge bayonets, fire at will, is about all that a private soldier knows of a battle.”

— Confederate Sam R. Watkins.

A gawky, lazy, dodger,

When came the conscript officer

And took me for a sodger.

He put a musket in my hand,

And showed me how to fire it;

I marched and counter-marched all day;

Lord, how I did admire it!

— This tune is “The Valiant Conscript” and it is sung to the music of “Yankee Doodle.”

“Our men are not sufficiently impressed with a sense of honor that it is better to die by fire than to run.”

— General William Hardee of the Confederacy.

“War is at best barbarism…Its glory is all moonshine. It is only those who have neither fired a shot, nor heard the shrieks and groans of the wounded who cry aloud for blood, more vengeance, more desolation. War is hell.”

— William Tecumseh Sherman. These words are from his June 19, 1879 address to the Michigan Military Academy.

“We made a bargain with them that we would not fire on them if they would not fire on us, and they were as good as their word. It seems too bad that we have to fight men that we like.”

— Words of a Union soldier.

Perhaps some of you reading the LearnCivilWarHistory.com blog are veterans or soldiers who know full well what it is like to under fire. However, for most us, we can only wonder and imagine what it is like to be “Seeing the elephant,” just as the young men of the Civil War wondered and imagined so many years ago.

Below are the experiences of being under Civil War fire as described by Captain Frank Holsinger. Try to imagine yourself in Captain Frank Holsinger’s shoes (or rather, brogans) as you read this stirring account of what it was like to be “Seeing the elephant” in the Civil War:

Excerpts from: How Does One Feel Under Fire? by Captain Frank Holsinger, 19th United States Colored Infantry

“My sensations at Antietam were a contradiction. When we were in line “closed en masse” passing to the front through the wood at “half distance,” the boom of cannon and the hurtling of shell as it crashed through the trees or exploding found its lodgment in human flesh; the minies sizzling and savagely spotting the trees; the deathlike silence save the “steady men” of our officers. The shock to the nerves were indefinable–one stands, as it were, on the brink of eternity as he goes into action. One man alone steps from the ranks and cowers behind a large tree, his nerves gone; he could go no longer. General Meade sees him, and, calling a sergeant, says, “Get that man in ranks.” The sergeant responds, the man refuses; General Meade rushes up with, “I’ll move him!” Whipping out his saber, he deals the man a blow, he falls–who he was, I do not know. The general has no time to tarry or make inquiries. A lesson to those witnessing the scene. The whole transaction was like that of a panorama. I felt at the time the action was cruel and needless on the part of the general. I changed my mind when I became an officer, when with the sword and pistol drawn to enforce discipline by keeping my men in place when going into conflict.

“When the nerves are thus unstrung, I have known relief by a silly remark. Thus at Antietam, when in line of battle in front of the wood and exposed to a galling fire from the cornfield, standing waiting expectant with “What next?” the minies zipping by occasionally, one making the awful thud as it struck some unfortunate. As we thus stood listlessly, breathing a silent prayer, our hearts having ceased to pulsate or our minds on home and loved ones, expecting soon to be mangled or perhaps killed, some one makes an idiotic remark; thus at this time it is Mangle, in a high nasal twang, with “D—–d sharp skirmishing in front.” There is a laugh, it is infectious, and we are once more called back to life.

“The battle when it goes your way is a different proposition. Thus having reached the east wood, each man sought a tree from behind which he not only sought protection, but dealt death to our antagonists. They halt, also seeking protection behind trees. They soon begin to retire, falling back into the corn-field. We now rush forward. We cheer; we are in ecstasies. While shell and canister are still resonant and minies sizing spitefully, yet I think this one of the supreme moments of my existence … The worst condition to endure is when you fall wounded upon the field. Now you are helpless. No longer are you filled with the enthusiasm of battle. You are helpless—the bullets still fly over and about you—you no longer are able to shift your position or seek shelter. Every bullet as it strikes near you is a new terror. Perchance you are enabled to take out your handkerchief, which you raise in supplication to the enemy to not fire in your direction and to your friends of your helplessness. This is a trying moment. How slowly time flies! Oh, the agony to the poor wounded man, who alone can ever know its horrors! Thus at Bermuda Hundreds, November 28th, being in charge of the picket-line we were attacked, which we repulsed and rejoiced, yet the firing is maintained. I am struck in the left forearm, though not disabled; soon I am struck in the right shoulder by an explosive bullet, which is imbedded in my shoulder strap. We still maintain a spiteful fire. About 12 M. I am struck again in my right forearm, which is broken and the main artery cut; soon we improvise a tourniquet by using a canteen-strap and with a bayonet the same is twisted until blood ceases to flow. To retire is impossible, and for nine weary hours or until late in the night, I remain on the line. I am alone with my thoughts; I think of home, of the seriousness of my condition; I see myself a cripple for life—perchance I may not recover; and all the time shells are shrieking and minie bullets whistling over and about me. The tongue becomes parched, there is no water to quench it; you cry “Water! Water!” and pray for night; that you can be carried off the field and to the hospital , and there the surgeons’ care—maimed, crippled for life, perchance to die. These are your reflections. Who can portray the horrors coming to the wounded?”At the completion of Captain Frank Holsinger’s military service, he was given a brevet rank of major. Holsinger settled in Kansas.