Virginia Secedes From The Union

April 17, 1861

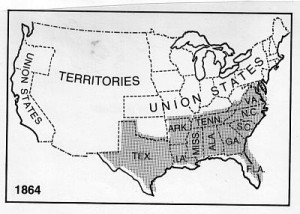

Secession fever hit the South after Abraham Lincoln was elected president. The South considered Lincoln’s Republican party victory in the 1860 presidential election as a sign that the North was now going to end the “peculiar institution” of slavery. For the South, the time of talk and compromise had ended. In December, 1860 South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union. Secession of the rest of the states that would make up the Confederate States of America occurred in two waves.

By the first week in February, 1861 six more states joined South Carolina in secession. The first wave of states to secede from the Union were all states of the Lower South. These states included: Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina.

The second wave of states to secede from the Union consisted of states from the Upper South. These states were: Arkansas, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia.

The Confederate States of America was made up of eleven states.

Order and Dates Of Secession of the Confederate States:

The First Wave – The Lower South

- 1. South Carolina – December 20, 1860

- 2. Mississippi – January 9, 1861

- 3. Florida – January 10, 1861

- 4. Alabama – January 11, 1861

- 5. Georgia – January 19, 1861

- 6. Louisiana – January 26, 1861

- 7. Texas – February 1, 1861

The Second Wave – The Upper South

- 8. Virginia – April 17, 1861

- 9. Arkansas – May 6, 1861

- 10. North Carolina – May 20, 1861

- 11. Tennessee – June 8, 1861

Virginia was a very important state of the Confederacy. The capital of the Confederacy was first in Montgomery, Alabama, but Richmond, Virginia soon became the Confederate capital. Virginia had 40 percent of the Rebel manufacturing capacity and the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond would produce most of the Confederate artillery during the Civil War. As part of the Upper South, Virginia was a resource of vital agricultural and industrial assets needed to supply the Confederate war effort.

Many of the South’s military leaders were of Virginia, such as: Robert E. Lee, Thomas J. Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart, Joseph E. Johnston, A. P. Hill, Richard S. Ewell, and others. The Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in Lexington provided many Rebel leaders of the Civil War. Along with North Carolina, and Tennessee, Virginia supplied most of the Confederacy’s soldiers. Richmond, Virginia is only 96 miles away from Washington D.C., and it was very important for the Confederacy to defend, and keep Richmond safe. Virginia was a hotspot of action during the Civil War. The First Battle of Manassas (First Battle of Bull Run was the name used for this same battle by the North) was the first major land battle of the Civil War, it was fought July 21, 1861, near Manassas, Virginia. General Robert E. Lee would surrender the Army of Northern Virginia to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia on April 9, 1865.

The Winchester, Virginia area is rich in both Civil War and colonial history. Winchester is located in the north-western part of Virginia in Frederick County. This area is part of the Shenandoah Valley, and Winchester was an important transportation and commercial center. During the Civil War, from early 1862 to late 1864, Winchester changed hands between North and South no less than 70 times. Six major Civil War battles were fought in the Frederick County, Virginia area. These six major battles include the First, Second, and Third Battles of Winchester, the First and Second Battles of Kernstown, and Cedar Creek.

The Shenandoah Valley of Virginia was a place of much action during the Civil War. A curiosity of the geography of the Shenandoah Valley is that as you go down the valley from north to south, you actually go up in elevation. So, as you go “down” the valley, you actually go “up.” The Shenandoah Valley was an important route of invasion into the North for the Confederates, and was a source of much needed provisions. It was important for the North to prevent the South from using the Shenandoah Valley.

When Virginia seceded, it took over the United States armory located at Harpers Ferry, Virginia and the Gosport Naval Yard in Norfolk. The Gosport Naval Yard was the largest facility of shipbuilding and repair in the Confederate States of America.

The Virginia Ordinance of Secession

AN ORDINANCE to repeal the ratification of the Constitution of the United State of America by the State of Virginia, and to resume all the rights and powers granted under said Constitution.

The people of Virginia in their ratification of the Constitution of the United States of America, adopted by them in convention on the twenty-fifth day of June, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty-eight, having declared that the powers granted under said Constitution were derived from the people of the United States and might be resumed whensoever the same should be perverted to their injury and oppression, and the Federal Government having perverted said powers not only to the injury of the people of Virginia, but to the oppression of the Southern slave-holding States:

Now, therefore, we, the people of Virginia, do declare and ordain, That the ordinance adopted by the people of this State in convention on the twenty-fifth day of June, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty-eight, whereby the Constitution of the United States of America was ratified, and all acts of the General Assembly of this State ratifying and adopting amendments to said Constitution, are hereby repealed and abrogated; that the union between the State of Virginia and the other States under the Constitution aforesaid is hereby dissolved, and that the State of Virginia is in the full possession and exercise of all the rights of sovereignty which belong and appertain to a free and independent State.

And they do further declare, That said Constitution of the United States of America is no longer binding on any of the citizens of this State.

This ordinance shall take effect and be an act of this day, when ratified by a majority of the voter of the people of this State cast at a poll to be taken thereon on the fourth Thursday in May next, in pursuance of a schedule hereafter to be enacted.

[Adopted by the convention of Virginia April 17,1861.]

[Ratified by a vote of 132,201 to 37,451 on May 23, 1861.]

Up, men, and to your posts! Don’t forget today that you are from Old Virginia!

— General George E. Pickett, to his men just before Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. Many of these men never returned to “Old Virginia.”