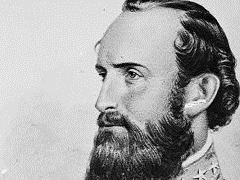

General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson Crosses Over the River

May 10th, 1863

At Chancellorsville during the night of May 2, Stonewall Jackson is struck three times by friendly fire. A bullet each to Jackson’s right hand and left wrist, and a third to his left arm between the shoulder and elbow. The third bullet fractured Jackson’s humerus bone and injured his brachial artery, this wound was very serious and it bled profusely. Doctors amputated Jackson’s left arm two inches below the shoulder early the morning of May 3.

As the days pass, Jackson is healing and recovering well from the amputation and other wounds. The prognosis for Stonewall’s recovery looked good.

Early the morning on May 7, Jackson awoke and complained of a sharp pain in his right side. A doctor’s examination determines that Stonewall has pneumonia. Since the amputation of his left arm Jackson had been alert and sharp of mind, but with pneumonia he became feverish, lapsing in and out of consciousness.

Sometimes Jackson would speak coherently with those around him, but at other times he was in a delirium… giving orders to subordinates as if he were still on a battlefield.

Mary Anna Jackson Arrives With Baby Julia

Jackson’s wife Anna was summoned to his bedside. Anna arrived on May 7, bringing little Julia with her, the Jackson’s five-month-old baby. Stonewall had seen baby Julia only once before. In Stonewall Jackson’s coherent and lucid moments he was able to visit with Anna and baby Julia, but his pneumonia was very dire and his condition continued to decline. By the morning of Sunday, May 10, the doctors knew the general’s time on earth was short.

Stonewall Jackson was a devout Presbyterian, his faith in God was the cornerstone of his life. In his personal habits Jackson neither drank or smoked. Anna was told her husband would not live through the day, she asked her dying love: “Do you not feel willing to acquiesce in God’s allotment, if He will you go today?” and Jackson replied, “I prefer it.” Anna continued, “Before this day closes, you will be with the Blessed Savior in his glory.” Jackson replied: “I will be an infinite gainer to be translated.”

As this Sunday in early May continued, Jackson’s condition worsened more and more. He was becoming weak and exhausted, his breathing difficult. Anna asked her husband if he realized that before sunset he would be with his savior. But Jackson thought otherwise and told his wife: “Oh no, you are frightened my child, death is not so near. I may yet get well.” Anna told her husband the doctors said there was no hope.

Always Desired To Die On Sunday

Jackson called for his doctor, saying to him: “Doctor, Anna informs me that you have told her that I am to die today.” The doctor answered: “That is so.” Jackson replied, “Very good, very good, it is all right.” Later, when his strength was further slipping away, Jackson spoke: “It is the Lord’s day; my wish is fulfilled. I have always desired to die on Sunday.”

At 1:30 in the afternoon Jackson’s doctor noticed the general was conscious, he told Jackson that he had only but a couple of hours left yet to live. Brandy and water were offered, but Jackson declined saying: “It will only delay my departure and do no good. I want to preserve my mind to the last.” Soon, the famed Confederate general’s mind was back in delirious confusion.

Stonewall first gave orders like he was on a battlefield, then like he was at a mess table talking with his staff, then with his wife and daughter, then he was at his prayers… all this while lying in bed with his mind clouded by unrelenting fever.

Let Us Cross Over The River And Rest Under The Shade Of The Trees

The Sunday of May 10, 1863 was a beautiful spring day at Guinea Station, Virginia, where a great Confederate general lay dying in a farmhouse bed. In the early afternoon, General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson spoke: “Order A.P. Hill to prepare for action! Pass the infantry to the front rapidly! Tell Major Hawks…”

After that Jackson paused, then with a smile he spoke his last words: “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

At 3:15 in the afternoon on May 10, 1863 Confederate General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson gained his infinite translation, making his way to eternity.

Lee’s Right Arm Is Gone Forever

Stonewall Jackson, General Robert E. Lee’s “right arm,” was now gone forever. The great Confederate victory at Chancellorsville, where Lee had gambled and won (this battle would become known as Lee’s “masterpiece”), had came with a tragic loss for Lee. Thomas Jonathan Jackson could never be replaced. In battles yet to come, General Lee and the Confederacy would sorely miss Stonewall Jackson and his aggressive leadership.

Stonewall Jackson’s Lexington, Virginia Home

The only home Stonewall Jackson ever owned is a brick house in Lexington, Virginia. Jackson owned this home before the Civil War as he taught at the nearby Virginia Military Institute (VMI). Today, the Stonewall Jackson House in Lexington is a Registered National Landmark and is open to visitors.A number of Jackson’s personal items are on display at his home. While in Lexington, you will learn much about Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson at VMI’s museum, where you may view the preserved Little Sorrel, Jackson’s horse.

Also in Lexington is the Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery. Jackson is buried there along with other Confederate veterans.

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!