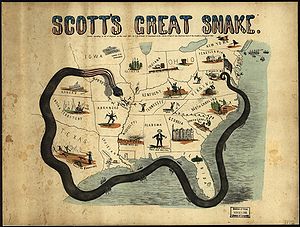

General-in-Chief Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was a strategy to blockade the South by sea, and gain control of the Mississippi River. This would split the South, and eventually deprive it economically.

General-in-Chief Winfield Scott And His Anaconda Plan

At the beginning of the Civil War, General-in-Chief Winfield Scott was seventy-four-years-old, so overweight he could not mount or ride a horse, and suffered from painful gout. Scott’s best days were behind him. Since the War of 1812, Scott had participated in all of America’s military actions. He was a genuine hero. There was no doubt about Scott’s leadership ability, in the War of 1812 he was once captured, and during the Mexican War he led the campaign that captured Mexico City.

His nickname was Old Fuss and Feathers, because of his reputation for strict adherence to regulations, and a propensity for fancy uniforms. Winfield Scott was born a Virginian in 1786, but was loyal to the Union. He did not understand Robert E. Lee’s choice to side with the Confederacy, and had even asked Lee to lead the United States Army.

President Abraham Lincoln sought Scott’s advice, however as the Civil War began, it was evident the aging Winfield Scott was not up to the demands of leading the army. At times, Scott would doze off during meetings. Scott voluntarily retired on November 1, 1861 and was replaced by George B. McClellan as general in chief.

On May 3, 1861 General-in-Chief Winfield Scott writes to General George B. McClellan describing his strategy for subduing the rebellion. Later, Scott’s strategy was derisively referred to as The Anaconda Plan:

Winfield Scott’s The Anaconda Plan

HEADQUARTERS OF THE ARMY,

Washington, May 3, 1861.

Maj. Gen. GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN,

Commanding Ohio Volunteers, Cincinnati, Ohio:

SIR: I have read and carefully considered your plan for a campaign, and now send you confidentially my own views, supported by certain facts of which you should be advised.

First. It is the design of the Government to raise 25,000 additional regular troops, and 60,000 volunteers for three years. It will be inexpedient either to rely on the three-months’ volunteers for extensive operations or to put in their hands the best class of arms we have in store. The term of service would expire by the commencement of a regular campaign, and the arms not lost be returned mostly in a damaged condition. Hence I must strongly urge upon you to confine yourself strictly to the quota of three-months’ men called for by the War Department.

Second. We rely greatly on the sure operation of a complete blockade of the Atlantic and Gulf ports soon to commence. In connection with such blockade we propose a powerful movement down the Mississippi to the ocean, with a cordon of posts at proper points, and the capture of Forts Jackson and Saint Philip; the object being to clear out and keep open this great line of communication in connection with the strict blockade of the seaboard, so as to envelop the insurgent States and bring them to terms with less bloodshed than by any other plan. I suppose there will be needed from twelve to twenty steam gun-boats, and a sufficient number of steam transports (say forty) to carry all the personnel (say 60,000 men) and material of the expedition; most of the gunboats to be in advance to open the way, and the remainder to follow and protect the rear of the expedition, &c. This army, in which it is not improbable you may be invited to take an important part, should be composed of our best regulars for the advance and of three-years’ volunteers, all well officered, and with four months and a half of instruction in camps prior to (say) November 10. In the progress down the river all the enemy’s batteries on its banks we of course would turn and capture, leaving a sufficient number of posts with complete garrisons to keep the river open behind the expedition. Finally, it will be necessary that New Orleans should be strongly occupied and securely held until the present difficulties are composed.

Third. A word now as to the greatest obstacle in the way of this plan–the great danger now pressing upon us–the impatience of our patriotic and loyal Union friends. They will urge instant and vigorous action, regardless, I fear, of consequences–that is, unwilling to wait for the slow instruction of (say) twelve or fifteen camps, for the rise of rivers, and the return of frosts to kill the virus of malignant fevers below Memphis. I fear this; but impress right views, on every proper occasion, upon the brave men who are hastening to the support of their Government. Lose no time, while necessary preparations for the great expedition are in progress, in organizing, drilling, and disciplining your three-months’ men, many of whom, it is hoped, will be ultimately found enrolled under the call for three-years’ volunteers. Should an urgent and immediate occasion arise meantime for their services, they will be the more effective. I commend these views to your consideration, and shall be happy to hear the result.

With great respect, yours, truly,

WINFIELD SCOTT.

Source:

Union Correspondence, Orders, And Returns Relating To Operations In Maryland, Eastern North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia (Except Southwestern), And West Virginia, From January 1, 1861, To June 30, 1865.–#3 O.R.–SERIES I–VOLUME LI/1 [S# 107]

The Press Mocks The Anaconda Plan

Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was criticized as too slow and gained its “Anaconda” name when the press mockingly compared it to a snake slowly constricting its prey to death. As Scott’s plan was being considered, the clamor in the North was for an invasion that would quickly crush the Confederate army presently found at a railroad junction in northern Virginia named Manassas. Taking Manassas would hurt the Rebels significantly as the railroad lines there were major ones that connected to the Shenandoah Valley, and the thus to the heart of the South.

Richmond, Virginia had become the Confederate capital, and the southern Congress planned a session there on July 20, 1861. The New York Tribune (published by Horace Greeley) responded with this headline:

FORWARD TO RICHMOND! FORWARD TO RICHMOND!

The Rebel Congress Must Not be

Allowed to Meet There on the

20th of July

BY THAT DATE THE PLACE MUST BE HELD

BY THE NATIONAL ARMY

After this, other newspapers throughout the Union followed suit with the FORWARD TO RICHMOND! thought and the public soon caught on to the fever. In light of this, even though Southern seaports were beginning to be blockaded, Scott’s plan faltered as public and political pressure demanded quick military action. President Lincoln saw merit in attacking the Confederates at Manassas. On July 21, 1861 the Battle of First Bull Run (called First Manassas by the Confederates) took place. It was a Union loss, no Union troops went on to Richmond, and most skedaddled back to Washington.

Soon the idea faded away that a quick, strong, and superior military action along with a compromising attitude, might end the Confederate rebellion fast. The Union would have to win the Civil War by destroying the Confederate armies on the field. Much time, many resources, and many, many lives would have to be spent to accomplish the Northern victory.

The Anaconda Plan Helped The North Win The Civil War

Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was worthy. Blockading the South’s seaports and gaining control of the Mississippi River were major factors in crippling the Rebel economy and military. As the Civil War progressed, the basic strategy of the Anaconda Plan contributed ultimately to the defeat of the Confederacy.

Old Winfield Scott lived to see the end of the Civil War. He died in 1866.