The “Peculiar Institution”

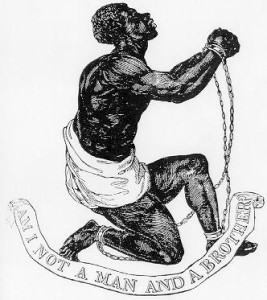

Slavery was a fact in the United States until the cleansing of the Civil War. The bloodshed of the Civil War brought an end to slavery and kept this nation as an undivided union of states. Slavery was the foundation cause of the Civil War. The evil, cruel, brutal, and abhorrent institution of slavery in the United States came to an end through the Civil War.

It is important to note that slavery was not unique to the United States. Many European countries had slavery before it came to the New World colonies and grew. Countries like Spain and Portugal had significant counts of slaves before 1492. But, this is no defense of the institution of slavery. The world was guilty of slavery.

It is important to note that slavery was not unique to the United States. Many European countries had slavery before it came to the New World colonies and grew. Countries like Spain and Portugal had significant counts of slaves before 1492. But, this is no defense of the institution of slavery. The world was guilty of slavery.

In 1619 a Dutch ship arrived at the Virginia colony and sold “20 and odd negroes” to colonists. Some of these blacks became indentured servants (people who worked for a period of years to pay for their passage to the New World, then became free) but others were slaves. Most blacks in the Virginia colony were either free or indentured servants in 1640. Slavery grew and flourished in the colonies, especially in the Southern ones. By 1700 in the Virginia colony, most blacks were in the bondage of that “Peculiar Institution.”

Slavery was a disease of humanity that spread to the colonies of the New World. It should be known that although the United States was guilty of slavery, it fought a war against itself to end this “Peculiar Institution” within its borders. As a result of the Civil War, in which brother literally fought against brother and hundreds of thousands died, slavery ended in the United States.

King Cotton

The South depended on slavery for its agricultural and economic success. Cotton was King in the South and the institution of slavery made it very profitable. Indeed, the South’s economy was based on slavery and cotton. One of the main contributing factors to the Civil War was that the South was willing to go to war with its own fellow countrymen in order to preserve the enslavement of other human beings.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

In 1808, the importation of slaves was made illegal in the United States of America. Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, as an outcry against slavery after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, slaves were described as victims of the Southern system. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book was a powerful factor in bringing about anti-slavery sentiment in the North, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was very popular book among abolitionists. The expansion of the country westward, with new territories and states coming into being, only fueled debate and conflict over the spread and continuation of slavery. When Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, the South believed he intended to end slavery. Secession, and the Civil War followed. Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold more copies than any book other than the Bible and caused Abraham Lincoln to exclaim upon meeting Harriet Beecher Stowe during the Civil War: “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war!”

In 1860, approximately 4,500,000 white people were living in the states that had slavery. Of these 4,500,000 approximately 46,000 of them owned more than 20 slaves. Approximately 4,000,000 slaves lived in America at the start of the Civil War. On January 1, 1863 President Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation that declared free the slaves in the parts of the country which were in rebellion. Only Northern victory and preservation of the Union ensured the end of slavery in the United States.

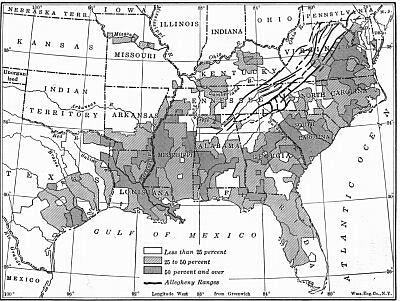

Distribution Of Slaves In The Southern States

The shown map is: Distribution of Slaves in the Southern States from the book History of the United States by Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard.

- White areas depict less than 25% slave distribution

- Light gray areas depict 25 – 50%

- Dark gray areas depict 50% and greater

Quotes By Abraham Lincoln Regarding Slavery

“In giving freedom to the slave we assure freedom to the free,–honorable alike in what we give and what we preserve.”

— Abraham Lincoln, from his Second Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862.

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving the others alone, I would also do that.”

— Abraham Lincoln, from a letter to Horace Greeley of August 22, 1862. (The Emancipation Proclamation had been written but not yet released).

“I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.”

— Abraham Lincoln, from a letter to Horace Greeley, August 22, 1862.

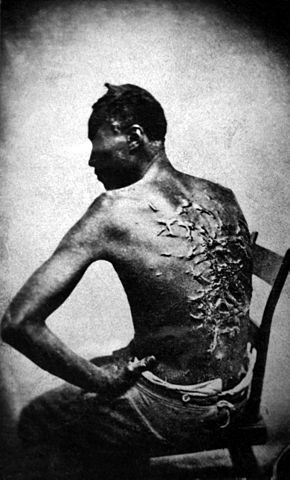

Slavery Was Cruel

The ugly fact is that slaves were treated as property. Slavery was a brutal, cruel, unfair, and evil thing. Slaves did not have the right to vote. Slaves could not own land. Slaves could not travel. Slave marriages were not recognized by law. Slaves were allowed to work, and work hard from the early morning light until darkness… or longer if the moonlight was bright.Slave families could be split up by the whims and desires of their owners. Slaves could be beaten and whipped to make them obey. Some slaves were killed either by their owners or by hard work. Disease killed slaves. Slaves worked on plantations and farms, in homes, on docks, in businesses, and anywhere labor was needed.

The history of slavery still haunts the United States to this day. Perhaps only with the coming of each new generation, with its hopefully new and unprejudiced rational understanding, will the scar of slavery completely fade away. That will be a glorious time.

Learn Civil War History Podcast Episode Seven: Freedman Jourdon Anderson Writes A Letter To His Old Master

Spotify