Ball’s Bluff – An Early Union Battle Disaster

October 21, 1861

“I want sudden, bold, forward, determined war.”

Senator Edward D. Baker’s reaction to Fort Sumter as he declared it to the Senate. Baker was a unique individual who would play a key role in the Battle of Ball’s Bluff.

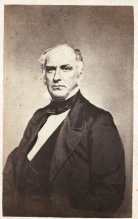

Edward D. Baker: A Man On The Move

When Edward D. Baker was four, his family moved from England to Philadelphia. Baker later lived in Illinois where he was admitted to the bar in 1830. In 1835, he started in local Illinois politics and along this path he met a young Abraham Lincoln.In 1837 Baker was elected to the United States Congress and in 1840 to the United States Senate. Edward D. Baker defeated Abraham Lincoln in 1844 for the United States congressional seat, and was elected. Despite their political competition Lincoln and Baker were good friends and later Lincoln named his second son, Edward Baker Lincoln, after him.

Baker was a veteran of the Black Hawk War of 1832 and in the Mexican War he served as a colonel of the 4th Illinois Volunteers. After this he moved to Galena, Illinois to run for the United States Congress, thus avoiding running against his friend Abraham Lincoln from Springfield whom he had previously defeated in political contest. Baker was elected to Congress, but he failed to obtain a cabinet appointment from President Franklin Pierce in 1852, so he moved on west to follow the California Gold Rush. Edward D. Baker was admitted to the bar in California.

In 1860 Baker was on the move again, this time to Oregon. Following in his tradition of political success, he was elected to the United States Senate. At Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration Edward D. Baker rode in the presidential carriage and introduced Lincoln before his inaugural address.

In May, 1861 Baker’s star once again was on the rise as the Civil War began to boil. He was authorized by the Secretary of War to form an infantry regiment that would be counted as part of the California quota. Baker raised the 71st Pennsylvania Infantry (also known as the 1st California) by mostly recruiting troops from Philadelphia and he served as the regiment’s colonel. Only a few month’s later, Baker gained command of a brigade in General Charles P. Stone’s division. Baker’s duty as brigade commander was to guard fords of the Potomac River north of Washington.

By the fall of 1861, Edward D. Baker was fifty-years-old. He was handsome, beardless, a close personal friend of President Abraham Lincoln, and a staunch Union supporter. He was both an Oregon senator and a colonel in the army. Baker had distinguished himself at many levels of law and politics, and now further achievement apparently awaited him as a Civil War officer.

Edward D. Baker was a man fond of reciting poetry who was always on the move, he was larger than life. Soon Baker would have the opportunity to “promote sudden, bold, forward, determined war.”

With a Civil War now underway, may God bless and protect any Confederate found in Colonel Edward D. Baker’s path of success and accomplishment.

Ball’s Bluff Civil War Battlefield

https://youtu.be/HR9vsK6VIo0

Ball’s Bluff

Ball’s Bluff is along the Potomac River about 35 miles northwest of Washington, D.C., and is northeast of Leesburg, Virginia. It is a steep 100-foot-high bank rising above the Potomac on the Virginia shore. In 1861 there was a 50-yard-deep floodplain from the river, and the bluff itself was about 600 yards wide. The steep and wooded bank of the bluff had a 10 to 12 foot-wide cow or cart path meandering from the shore up to the top.

Approximately halfway across the Potomac River from Ball’s Bluff and toward the Virginia shore, is Harrison’s Island. The water runs swiftly through this narrow channel between Ball’s Bluff and Harrison’s Island. From Harrison’s Island across the Potomac over to the Maryland shore, the channel is wider and shallower.

General George B. McClellan Takes Action

After First Bull Run, the Confederates were firmly planted and in control of most of northeast Virginia. In October, CSA General Joseph E. Johnston had accumulated the majority of Confederate troops at Centerville. There were still some Rebel troops around Leesburg north of Centerville, but there were rumors floating about that Johnston was pulling his Leesburg men back (a black deserter of the 13th Mississippi had told that the Confederates at Leesburg had removed supplies back to Manassas, thus preparing for a retreat).

Union General George B. McClellan thought it might be worthwhile to see how sincere Johnston was about keeping troops at Leesburg. Camped at Langley on the Virginia side of the Potomac was the Pennsylvania Reserves division and it had 13,000 troops led by George McCall. McClellan sent McCall to Dranesville (about halfway between Leesburg and Washington, D. C.) on October 19, thinking this advancement of Yankee troops might help urge Joe Johnston to move his troops out of Leesburg.

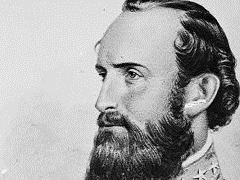

Contrary to McClellan’s expectations, instead of withdrawing Confederate commander Nathan “Shanks” Evans took up a defensive position west of Dranesville. Then to further complicate the situation, on the morning of October 20 McClellan received an incorrect message saying the Confederates had responded to McCall’s movement by withdrawing. Shanks Evans’s defensive actions west of Dranesville were misinterpreted as a withdrawal.

General Charles Stone Moves Troops

McClellan wanted to be sure about the Confederate retreat, so he sent an order containing these words to General Charles Stone on the Maryland side of the Potomac:

“…keep a good lookout upon Leesburg, to see if this movement has the effect to drive them away. Perhaps a slight demonstration on your part would have the effect to move them.”

General Stone interpreted McClellan’s orders freely and proceeded to cross a regiment or two at Edward’s Ferry below Ball’s Bluff, and sent other troops three miles up the Maryland side of the Potomac so they could cross over to Virginia at Harrison’s Island. Stone’s thoughts were that he could apply some pressure to the Confederates and urge them to retreat from Leesburg.

Where Are The Rebels? How Many Are There?

Stone’s men marching toward the crossing at Harrison’s Island were the 20th Massachusetts. It was a nighttime march and by midnight they found themselves making the crossing from the Maryland shore. This crossing was difficult and slow because they only had three small boats that could only ferry a combined total of 25 men at a time. There was a lot of standing around, waiting, and confusion for those men waiting to cross and for those who had crossed over the river.

Near dawn on October 21, all the 20th Massachusetts found itself on Harrison’s Island and looking out at the remaining river crossing of 150 yards over to the Virginia shore. Beyond the river there was a high and wooded bluff, Ball’s Bluff was its name. They also learned that the previous evening the 15th Massachusetts had moved five companies over to the Virginia shore. Those men were now up on the high bluff and something was going on up there.

The 20th Massachusetts continued on and made its crossing from Harrison’s Island, then it climbed up Ball’s Bluff by the meandering cow or cart path. At the top they found themselves in a glade of open ground and not much seemed to be going on. That dawn, Colonel Charles Devon of the 15th Massachusetts had taken some troops almost all the way to Leesburg, west of Ball’s Bluff. Devon ran into some Confederate outposts during his foray and some shots were fired. Devon was now back at the glade.

Confederates were off somewhere in the woods beyond the glade and on higher ground. There were some pickets doing some shooting. No one knew exactly where the Rebels were, nor how many of them there might be. Colonel Devon sent word off to General Stone, reporting what he knew. Stone sent word back telling Devon to wait for Colonel Edward D. Baker, who would arrive soon with more troops and he would take charge.

Colonel Edward D. Baker Takes Charge At Ball’s Bluff

After some delay, Colonel Baker arrived at Ball’s Bluff and took command, ready to satisfy his want of: “sudden, bold, forward, determined war.” Abraham Lincoln’s close friend was now in charge, ready to move (Remember, Baker was always a man on the move!) against the Confederates. One can only imagine how much Baker, the successful lawyer and politician, had longed for this moment.

Edward D. Baker was known to occasionally recite poetry, and once on a battlefield had told a friend to:

“Press where ye see my white plume shine amidst the ranks of war.”

As Baker assumed command he told Colonel Devon, “I congratulate you, sir, on the prospect of a battle,” and to the troops nearby he inquired, “Boys, you want to fight, don’t you?” The boys responded positively. The fight was on.

The Battle of Ball’s Bluff Video

https://youtu.be/rlJTny3MFpI

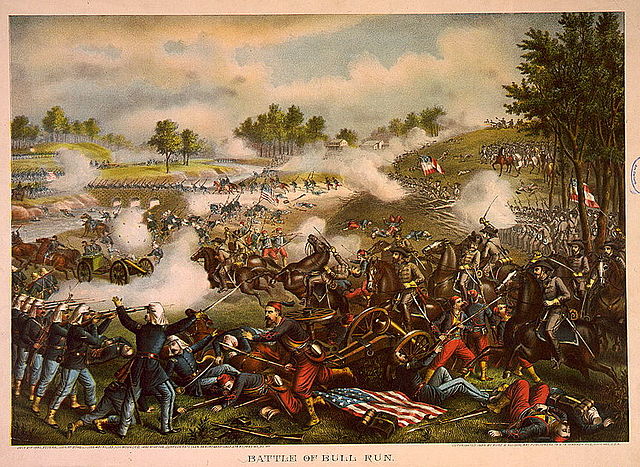

Seeing The Elephant

The Rebel fire was becoming more and more frequent. The Johnny Rebs were concentrating in greater numbers on the high ground beyond in the woods. Baker had moved a couple of guns up on the bluff and they were put to work shelling the woods from where the Rebel sniping fire came. The 20th Massachusetts returned fire, but men were being hit and falling to the ground. The troops were green and new to the idea that the enemy shot back at them, and with accuracy too. The men felt their nerves frazzle as they saw the elephant first-hand. This was no camp practice drill, blood flowed and lives were ending.

Colonel Milton Cogswell

Baker returned to the edge of the bluff and saw the New York Tammany Regiment making its way up the path. With the arrival of the Tammany men, there would be a total of four Union regiments on Ball’s Bluff. Colonel Baker felt more and more confident. Upon seeing Colonel Milton Cogswell of the Tammany Regiment approaching the top of the bluff, Baker waved and greeted the colonel with a line from Sir Walter Scott’s “The Lady of the Lake“:

“One blast upon your bugle horn is worth a thousand men.”

Colonel Milton Cogswell of the Tammany Regiment was not a lawyer and politician turned officer. Cogswell was a genuine professional soldier from West Point and he saw the situation at the top of Ball’s Bluff much differently than Colonel Edward D. Baker. To Cogswell’s trained military eye, things looked bad. Very bad.

A Turkey Shoot

The Confederates held the high ground in woods, brush, and timber, and they were picking off Union men at will. It was like a turkey-shoot. Cogswell knew the Confederates were building up to an attack and fearfully the Union men were backed up to a steep bluff with an unfordable river below. To increase the trouble that Cogswell anticipated, soon one of the guns recoiled over the cliff’s bluff. The Rebels had already silenced the other gun with sniper fire and now the Union men were left with no big gun.

Colonel Edward D. Baker’s Death

Colonel Edward D. Baker may have been a lawyer-politician made into a colonel, but he was not an idiot. Baker immediately caught on to the dire circumstances facing the Union men. He moved along the Union line encouraging the troops to stand fast.Perhaps Colonel Edward D. Baker realized that if they retreated down the bluff, then there were only three small boats waiting to ferry everyone across the river. It would take hours to cross back over the river and they would be at the non-existing mercy of Rebels firing down on them from Ball’s Bluff. It was better to stay and fight.

Certainly, Baker must have had a plan in mind for success, and to save the day for the Union. We’ll never know.

A Rebel sharpshooter, perhaps one not fond of poetry, drew a bead on Colonel Edward D. Baker and killed him instantly with a bullet through the brain.

The Battle Is Lost For The Union

The Union men had lost their poetry quoting lawyer-politician turned colonel. Baker’s body would now be on the move back down Ball’s Bluff. Things began to erode into a complete skedaddle for the men in blue. After all, how can you conduct a battle on a bluff where you are sitting ducks, without inspiring poetry recitation?

Some resistance and maneuvering was attempted, but as dusk came the day was lost for the Union. As Mississippians and Virginians shot at the compacted group of Yankees, men went over the bluff as fast as they could. Union men toppled over the bluff and in their haste to flee they fell agonizingly onto the bayonets and heads of others making their way down. The sides of the bluff were worn down to the dirt, and made smooth by men and bodies. More horror awaited them after they made it down to the river’s narrow shore.

All day long the wounded were coming down the bluff for evacuation, and now two boatloads of wounded soldiers were trying to make their way over to Harrison’s Island. Rebel bullets fired from the bluff above turned the water: “as white as in a great hail storm” as one man described. The boats were soon swamped by panicked men climbing on board in their rush to save their lives.

Many of the wounded of the swamped boats could not help themselves, they drowned and were swept downstream. A remaining sheet-metal skiff soon sank after being shot full of holes. Now there were no boats.

Night fell with bright and scarlet muzzle flashes continuing from high above. Some Union troops surrendered, some stripped down and swam to safety, others found a neck-deep ford and made it over to Harrison’s Island. Finally, over 200 Union men were killed or injured and over 700 were taken prisoner. The Confederate losses were minimal.

Sadness For Abraham Lincoln

Ball’s Bluff was a Union disaster. A day that was once interlaced with poetry, was now more appropriate as a subject for a dirge.

Back in Washington, bodies from Ball’s Bluff would float downstream and gather on the Potomac. Abraham Lincoln would now mourn a Union loss and the death of a close friend.