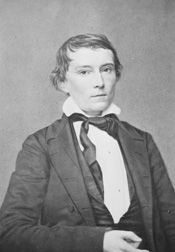

Alexander Hamilton Stephens: February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883

“A little, slim, pale-faced consumptive man just concluded the very best speech of an hour’s length I ever heard.”

–Illinois Congressman Abraham Lincoln describing Alexander Hamilton Stephens of Georgia after Stephens completed a speech to Congress. Lincoln and Stephens became friends while they served in Congress before the Civil War, but later slavery ended their friendship. During the Civil War, Stephens was the vice president of the Confederacy.

Little Aleck

Alexander Stephens was never a picture of health. He was 5′ 7″, a height in line with the norms of the 19th century, but only carried about ninety-pounds on his frame, he was pale and sickly. From birth, he was small, and during his childhood was given the nickname of “Little Aleck.” Stephens suffered many maladies including angina, bladder stones, colitis, migraine headaches, pneumonia, pruritus, arthritis, and sciatica. The word cadaverous would come to mind when seeing Alexander Stephens. He clothed himself layer upon layer trying to stay warm, and once defined his idea of happiness as; “To be warm.”Despite Stephens’s sickly body, behind his dark eyes he was blessed with a brilliant mind. His childhood was a difficult one, Stephens’s mother died soon after he was born, then his farmer and schoolteacher father died when Little Aleck was 14-years-old. Fortunately, a few benevolent mentors realized the potential of the highly intelligent young Stephens and funded his education at Franklin College (later to become the University of Georgia). Alexander Stephens finished at the top of his class at Franklin College.

Stephens became a lawyer and owned a plantation named Liberty Hall. If there can be such as thing as a good master, then perhaps Stephens was. He never beat or whipped his slaves, and he never split slave families apart. None of his slaves tried to escape, perhaps a testament of his care for them. Nonetheless, Stephens held human beings captive as slaves on his Georgia plantation and profited from their bondage.

Congressman

Alexander Stephens served in the United States Congress for 17 years and became an authority on the Constitution. Though he had an odd, girl-like, high voice, his brightness brought him fame as an orator. Stephens was a moderate Unionist and voted against Georgia’s secession. When Georgia did leave the Union, out of honor Stephens chose the South.

The new Confederate Congress met in Montgomery, Alabama (later Richmond, Virginia became the Confederate Capital) in February, 1861 to establish the foundation of the Southern country. Although he at first was opposed to disunion, Alexander Stephens was a favorite to become the president, but he lost that position to Jefferson Davis. Instead, Stephens became the vice president of the Confederate States of America.

On December 22, 1860 Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter marked as “For Your Eyes Only” to Georgia Congressman Alexander Stephens. In this letter Lincoln, before taking office, is telling Confederate Vice President Stephens in a private, personal letter, that he has no plans for his Republican administration to interfere with slavery:

“The South would be in no more danger in this respect, than it was in the days of Washington. I suppose, however, this does not meet the case. You think slavery is right and ought to be extended; while I think it is wrong and ought to be restricted. That I suppose is the rub.”

Stephens had been a Unionist, but he was also loyal to the South. A moderate, he was a supporter of a peaceful resolution between the North and the South, he hoped to avoid war. Seeing that it was inevitable, he became a supporter of secession.

As the South formed its government at the Montgomery Convention, Alexander Stephens contributed significantly to the creation of the Confederate Constitution. He chaired the Rules Committee and also the Committee on the Executive Departments.

Cornerstone Speech

Stephens gave what is known as his Cornerstone Speech on March 21, 1861 at Savannah, Georgia. This speech is probably what Stephens is best known for. In this speech, Stephens fundamentally lays out what the conflict between the North and the South is all about. One sentence (that gives the speech its name) of this extemporaneous speech stands out as the definition of the Confederate cause and what its government stood for:

“Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner- stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

— Vice President of the Confederacy, Alexander Hamilton Stephens.

With these words from his Cornerstone Speech, Alexander Stephens is stating in a nutshell the reason for secession … slavery. In our modern world of today, these words by Stephens are shocking and ugly. His words are so contrary to our times, that it may be necessary to read them twice, to see if what you thought he said, is really what he said. Stephens’s words show the way it was back in Civil War times. Because of this cornerstone difference between the North and the South, a brutal war of brother against brother was fought.

Soon there was conflict between Vice President Stephens and President Jefferson Davis. As Stephens was a moderate, he disagreed with Davis over various topics. The two Confederate leaders did not get along. Stephens refused to go on several missions that Davis wanted him to make. Finally, Davis had to order Stephens to go to the still independent state of Virginia as a Confederate commissioner.

Stephens remained a strong supporter of state sovereignty, so he disagreed with Davis over the Confederate draft and the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. Alexander Stephens continued to support negotiated peace, this gave Davis an edge in weakening Stephens’s strength within the Confederate government. Stephens’s role in the Davis administration was minimal and he felt that Davis ignored whatever advice or council he offered. For months at a time, Little Aleck was absent from Richmond, he would be at his Liberty Hall plantation in Georgia, avoiding the problems and cares of the Confederate government.

Peace Missions

Davis was able to get Stephens out of Georgia long enough to send him on a peace mission to Washington to meet with President Lincoln in 1863. It was Stephens’s idea that by June, 1863, with the success of Southern armies, and the “failure of Hooker and Grant,” (in Stephens’s words) that the timing was right for peace negotiations. Alexander Stephens offered to meet with President Lincoln, his old pre-war friend from their days in Congress, under a flag of truce to talk about prisoner-of-war exchanges. It was hoped that this tact of approach might lead to discussion of peace. Jefferson Davis liked the idea and gave Stephens instructions that limited his powers to prisoner exchanges.

On July 3, 1863 Stephens took a boat down the James River, on his way to Washington to meet with President Abraham Lincoln and to hopefully discuss peace. Also on that July 3 day, at a town named Gettysburg, the Army of Northern Virginia led by General Robert E. Lee suffered a climatic loss to General George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac.

President Jefferson Davis was expecting a Confederate victory at Gettysburg and thought that as the Army of Northern Virginia was approaching Washington from the north, that Vice President Stephens would be approaching from the south … and with good timing, they both might arrive at the same time. President Lincoln would then have a choice (and either way, the Union loses), discuss peace negotiations with Stephens, or suffer conquest by Robert E. Lee.

Things flip-flopped fast. The Union won at Gettysburg, President Lincoln got word at the same time of the Union battlefield victory, and that Confederate Vice President Stephens was coming to Washington on a mission. Lincoln sent word that refused a request of Stephens’s to pass through the lines under a flag of truce. Lincoln thought if the Confederacy wanted to discuss prisoner-of-war exchanges, then there were military ways for that. The fortunes of war had changed and Stephens’s mission was for naught.

Alexander Stephens met with President Lincoln in another peace attempt, at the Hampton Roads Peace Conference on February 3, 1865 as the Civil War was soon coming to an end. Confederates Stephens, Senator Robert M. T. Hunter, and Judge John A. Campbell met with Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward on board the steamer River Queen in Hampton Roads.

The three Confederates wanted Southern independence, Lincoln and Seward refused any plan that continued slavery. For Little Aleck, this meeting proved to be a total failure. Jefferson Davis knew that this meeting would prove fruitless for Alexander Stephens, and humiliate him. Stephens had to return to Richmond for a report of the meeting’s failure to the Confederate Congress, thus proving that Stephens’s interests in a negotiated peace were impossible.

Postbellum

At the end of the Civil War, Stephens was imprisoned at Boston’s Fort Warren. The year after being released from prison he was elected as a United States Senator of Georgia, but was denied his seat in Washington. Afterwards, Little Aleck bought the Atlanta Southern Sun, and wrote A Constitutional View of the Late War, in this 2 volume book he was critical of Jefferson Davis.

Stephens’s public service was not yet complete, he returned to the United States House of Representatives from 1873 to 1882. He was elected as governor of Georgia, but died within only a few months of taking office.

Alexander Hamilton Stephens is buried at his Liberty Hall plantation near Crawfordville, Georgia.

Alexander Stephens Quotes:

“We are without doubt on the verge, on the brink of an abyss into which I do not wish to look.”

–Alexander Stephens, after Abraham Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860.

“This step, secession, once taken, can never be recalled. We and our posterity shall see our lovely South desolated by the demon of war.”

–Alexander Stephens, January 18, 1861.

“It will probably end the war.”

–Alexander Stephens, regarding the secession of Virginia from the Union on April 17, 1861.

“We shall be in one of the bloodiest civil wars that history has recorded.”

–Alexander Stephens after Fort Sumter.

“War I look for as almost certain … Revolutions are much easier started than controlled, and the men who begin them … themselves become the victims.”

–Alexander Stephens, 1861.